By Roger Russell

These pages are copyrighted.

No portion of this site may be reproduced in whole or in part

without written permission of the author.

![]()

What's on This Page

![]()

Capturing the good old days of Hi-Fi

Back in the late 1940's and early 1950's I

shared the enthusiasm of a new word called "High Fidelity". It had a

unique meaning. We were all familiar with the sound of our table radios that we

spent lots of time listening to. Of course radio

programs were a major source of entertainment for me and for millions of others

back then. But something new was appearing. It was sound with better lows and

highs--something that a single 5 inch table radio

speaker or 12 inch console speaker could not do by itself. The dynamic range

and extended frequencies for bass drums and cymbal crashes were clearly audible

became very exciting.

The new and varied equipment was fascinating. I spent hours going through equipment catalogs and magazines and learned many of the different names like Acrosound, Altec, Ampex, Audak, Audiotape, Bell, Berlant, Bogen, Bozak, Brociner, Brook, Browning, Collaro, Collins, Concertone, Craftsman, Eico, Electro-Voice, Fisher, Garrard, Gately, GE, Grommes, Heathkit, Klipsch, Lafayette, James B. Lansing, Jensen, Livingston, Magnecord, McIntosh, Meissner, Newcomb, Pentron, Pickering, Pilot, Presto, Rek-O-Kut, Scotch, Scott, Stancor, Stephens, Stromberg-Carlson, Tech-Master, Triad, University, UTC, VM, and Weathers. There were many more. I marveled at the technical words, and pondered selecting a component that held the promise of even clearer dynamic sound. There were tuners that might grab even more distant stations; speakers that could maybe have deeper bass, perhaps that I could even feel, and higher highs; and amplifiers that could play louder without distortion.

In those days it is like riding a new magic

wave of music brought to life by special mysterious painted metal boxes and

glowing filaments enclosed in glass. They were made up of tubes, sockets

condensers, resistors, filter cans, transformers and high voltages. There was a

plethora of metal, plastic and Bakelite knobs and switches. Across the room

were large wooden cabinets containing drivers with black paper cones still

smelling of adhesives from behind plastic woven grille cloth. With AM radio

forgotten, there was the thrill of turning the FM tuner knob through the

interstation hiss to discover another high fidelity

station with the clear clean sound of music. There was the gymnastic trick of

waltzing around the room with a dipole antenna to find a better spot for

reception and ultimately being resigned to putting up a multi-element outdoor

Yagi antenna. There was the illuminated glass tuner dial that lit up the room

at night and the sound that came from the other side of the room from where you

sat in control, knob in hand.

The part that hooked me most was being able to capture those sounds from the radio and listen to them any time I want and as often as I want. The first recording I made was Aaron Copeland's Quiet City. Here was the fascination of brown plastic tape that went from one reel to the other and somehow carried those precious sounds.

There was also the search for records, popular or classical, that had the best dynamics, lowest notes and the smoothest extended highs that could exercise the capabilities or limitations of my system. Names like Angel, Audio Fidelity, Bartok, Columbia, Everest, Hi-Fi Records, London ffrr (full frequency range recording), Mercury Living presence, RCA Living Stereo, and Westminster were sought after. There was also Emory Cook's binaural records that were well known. Some radio broadcasts were live like Toscanini, WQXR string quartet and the Godina opera hour. They sounded exceptionally good.

There was also the distress of newly acquired scratches on our favorite records and the plague of dust that could too easily be seen in the bright light of day. Then there was the graduation from the 33/45/78 changer and turnover crystal cartridge to a new scientific world of separate turntable and arm and, of course, a new magnetic cartridge.

And now we think of these good old days when listening to hi-fi was new and inspiring. Today we may even try to find some of those old speakers and amplifiers and tuners to relive those memories and recapture those sounds. Alas, it's not what we thought. We are not the same people we were then. Our values, outlook, experience and even our hearing are not the same. The magic of rediscovering the past is mainly for the memories. Sometimes the sound is still very good, but often not as good as what we have now or what we thought we remembered.

![]()

My interest in music began when I was very little and my parents and I were living in Rumford, RI. I had a wind-up acoustic Victrola phonograph that used steel needles, which had to be replaced very often. The needle motion drove a diaphragm in the arm. The arm was hollow and formed part of a horn that continued to expand to the base of the arm and then to a larger section inside the cabinet of the phonograph. This horn was the amplifier and no electronics were involved. I had several 78rpm records like Snow White and The Three Little Fishes.

My father was a fire insurance engineer, but he had a hobby of ham radio, as did my mother's father. My father built his entire transmitter in a six-foot high steel rack and, of course, I could see much of the progress.

Sometime before 1943, my father bought a Stromberg-Carlson radio-phonograph console. It had a pullout drawer containing a 78rpm record changer. The radio could receive not only the broadcast band but also several short wave bands. The FM stations were on the 41-50MHz band. Shortly after, the frequencies were changed to the 88-108MHz band. My father bought a Pilot FM converter for 88-108MHz that sits on top of the console. He often played Dvorak's "New World" or Ravel's “Bolero” that was on 78rpm records. To me, it is obvious this was how my interest in electronics and sound had started.

In 1943, we moved to Scarsdale, NY. I had an Arvin AM radio with a wood case. I spent hours and hours listening to radio programs. I also listened to WQXR in NY City that played only classical music. Our violin class in grade school attended one of the WQXR live broadcasts. By then, I had added many Spike Jones records as well as “Peter and the Wolf’ to my collection.

After hearing some hi-fi demonstrations, I became totally obsessed to pursue clear, smooth undistorted sound--sound as clear and accurate as the real world violin that I played. Good recorded sound at high levels was particularly hard to find. I knew what it should be like because I later played in the high school orchestra. That was loud! I had also been very impressed with the Disney film FANTASIA. Although Stravinsky and Beethoven may have opposed such a combination of animation with their music, it increased my interest and appreciation of classical music that I might never have otherwise experienced.

By 1950, and operating with a limited budget, my first audio system purchase consisted of a General Industries 3 speed turntable and motor assembly and I mounted it on a board and base that I made out of plywood. There was a lever to change speeds from 78 to 45 and 33-1/3 rpm. It cost about $7.00. I mounted an arm with a crystal cartridge on the board. I also put in a power switch and a neon indicator light in the base.

|

|

|

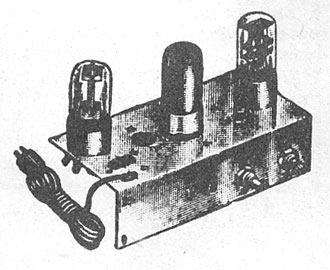

The amplifier was a three-tube ac-dc amplifier that I bought assembled. It had a 50L6 output tube, a 12SQ7 amplifier and a 35Z5 rectifier. It had a tone control and a volume control. I mounted a 6" speaker in a Webster cigar box to use with it. I bought several 78rpm record albums, like Rachmaninoff's “Isle of the Dead,” and some new Columbia LP's to play like Mozart's “Symphony No. 40,” Stravinsky's “Le Sacre du Printemps” and Mossourgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition.”

It wasn't long before I became dissatisfied with this sound and built several different amplifiers from Radio-TV News articles. I bought an aluminum chassis and a chassis punch and did all the construction from scratch. The best amplifier had 6V6's and 6SN7's. To go along with this, I purchased a VM record changer. Then, I didn't have to get up and change the 78rpm records every few minutes. It had a turnover crystal cartridge.

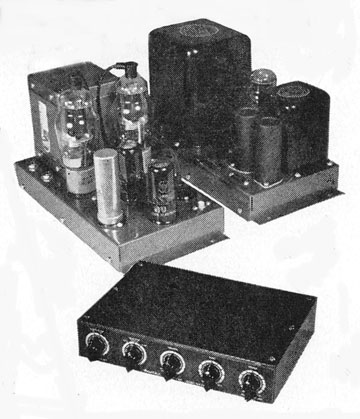

After having a summer job in 1951, I was able to think

about getting a better system. I bought my first major piece of Hi-Fi

equipment. It was the new Heath WA-A1 twelve watt amplifier

and WA-P1 preamplifier. They were very expensive at $69.50, including the

preamp. The shipping weight was 34 lbs. The amplifier had 807 output tubes that

had plate caps. The Peerless output transformer was made by Altec. The

amplifier consisted of two chassis, the power supply and the power amplifier.

Power for the preamp came from the power supply chassis of the amplifier.

After having a summer job in 1951, I was able to think

about getting a better system. I bought my first major piece of Hi-Fi

equipment. It was the new Heath WA-A1 twelve watt amplifier

and WA-P1 preamplifier. They were very expensive at $69.50, including the

preamp. The shipping weight was 34 lbs. The amplifier had 807 output tubes that

had plate caps. The Peerless output transformer was made by Altec. The

amplifier consisted of two chassis, the power supply and the power amplifier.

Power for the preamp came from the power supply chassis of the amplifier.

Later, I upgraded the amplifier to 5881's that did not require plate caps. If I had wanted to spend more money, I could have bought a new output transformer and upgraded to ultra-linear operation and 25 watts. At the time, I didn’t need the extra power. I replaced the record equalizer switch in the preamp, which had only a few selections, with a 17-position switch that had many other choices.

|

|

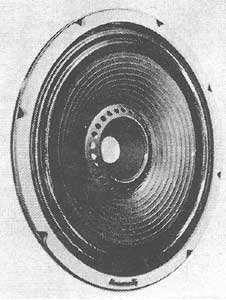

“Exceptional dispersion of high frequencies is a feature of the University Diffusicone-12, a 30 watt speaker designed to fill the need for a high quality in the moderate price field. High frequency response extends beyond 13,000 cps. The "diffuser" element provides dual horn loading of the speaker apex, thus substantially increasing efficiency in the upper frequency range, at the same time affording radial projection and aperture diffusion to assure reception of the speaker's entire range of reproduction irrespective of the listener's location. Constructional features include a 1-1/2 lb. Alnico V magnet and a 2-in voice coil. Design of the Diffusicone-12 permits replacement of either the diaphragm-basket assembly, or the magnet, in a matter of minutes with an ordinary screw driver the only tool required. A complete catalog sheet, including cabinet drawings, will be supplied on request to University Loudspeakers, Inc., 80 S. Kensico Ave., White Plains, NY.” |

I also purchased a University Diffusicone 12" speaker that had an unusual whizzer arrangement with multiple holes in the center to extend high frequencies. The University Loudspeaker factory was located in White Plains, just four miles from home. The whizzer did not add enough highs and I later added a University 4401 tweeter to the system to get more highs. Little did I know at the time that it had a peak in the response at about 11kHz.

|

|

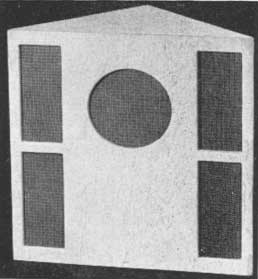

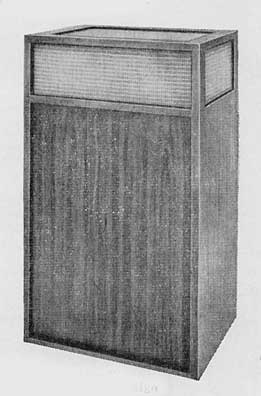

“CABINART MODEL 61: You high fidelity fans can assemble your own acoustically engineered folded horn corner speaker enclosure from a fine Cabinart kit. Save up to 50% and more on the unusual complete models by less than two hours of simple assembly. Enjoy a full extra octave of full clean bass never reproduced by the ordinary cabinet. Kit includes everything you need--5/8" pre-cut select white gum plywood--pre-cut speaker opening, grille cloth, Kimsul acoustic insulation, hardware, assembly and finishing instructions. Model 61 for 12" speakers: 32"H, 32"W, 16"D Weight 26 lbs. $19.95.” |

The corner baffle was a Cabinart kit that I put together. It came complete with grille cloth and acoustic material. It had to be placed in a corner, which acted as the rear part of the enclosure.

About this time Mercury records came out with the Living Presence series of records that had good dynamic range. One of the first records I bought was Tchaikovsky's sixth symphony. These were in mono, but after a few years, began to appear in stereo. The stereo versions were recorded using a three-microphone technique and today are highly sought after. The recordings have been reprocessed for CD and reissued.

Over the years I bought electronics parts from Westchester Electronics on Mamaroneck Ave. in White Plains. My favorite salesman was Gary Gilbert. Later, Gary went to work for Thruway Electronics which was close to Sonotone in Elmsford where I worked starting in 1959.

I bought my first tuner, a Meissner 8C, from a friend at school and later added a magic eye tube in a little box on top to give better tuning accuracy. The cabinet was wood with a nice finish to it. The sensitivity was really bad at 40uv, but I was close to New York City and I was using an outside TV antenna so I could still get good reception.

Later, I bought a Heath WA-P2 preamp that replaced the older WA-P1 preamp. I assemble it while I was on vacation at Cape Cod. This preamp also got power from the power supply in the WA-A1 amplifier using an octal plug.

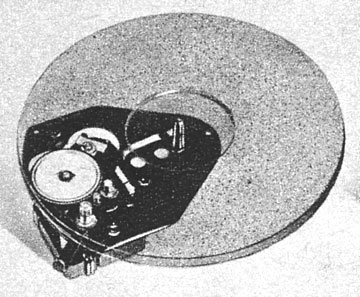

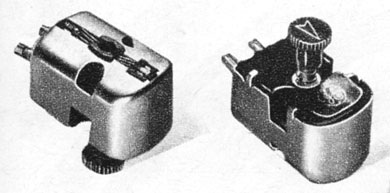

I replaced my VM changer with my first good changer, a

Garrard RC-80. It behaved like a really nice piece of precision equipment. I

installed a GE RPX-050 dual needle cartridge. Later, I replaced this cartridge

with a Fairchild 220. The 220 had a strong magnetic field and was attracted to

the steel turntable platter, practically crushing the stylus assembly. I had to

get a 1/4" thick foam mat for the turntable. When the Fairchild 225A came

out, I replaced it with that. The stray magnetic field problem had been

corrected by then.

I replaced my VM changer with my first good changer, a

Garrard RC-80. It behaved like a really nice piece of precision equipment. I

installed a GE RPX-050 dual needle cartridge. Later, I replaced this cartridge

with a Fairchild 220. The 220 had a strong magnetic field and was attracted to

the steel turntable platter, practically crushing the stylus assembly. I had to

get a 1/4" thick foam mat for the turntable. When the Fairchild 225A came

out, I replaced it with that. The stray magnetic field problem had been

corrected by then.

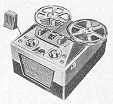

My first tape recorder was a Revere T-100 that I bought from my school friend who was getting a Pentron two-speed recorder that took 7" reels. The Revere took only 5" reels and ran only at 3-3/4 ips. The speaker was built into the recorder. The first recording I made was of Aaron Copland's Quiet City. That was very impressive.

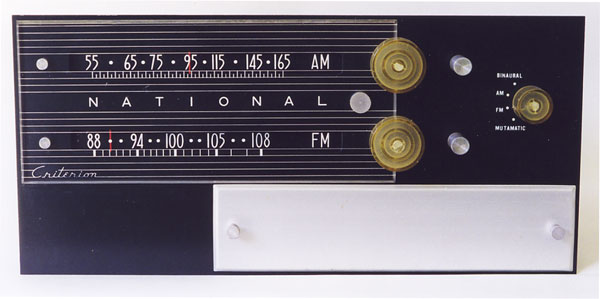

About this time my father decided to replace the Stromberg -Carlson console with a Thorens semiautomatic direct drive turntable, a GE RPX-050 cartridge, a National Criterion binaural tuner with a plug-in preamp and a 15" Altec 604C speaker in a large bass reflex cabinet. I made a Stancor 12-watt amplifier for him to use with it.

I later purchased a Pentron

9T-3C two speed machine and it cost $119. This handled 7" reels and had

speeds of 3-3/4 and 7-1/2 ips. I bought it at High

Fidelity Centre near the Pix theater in White Plains. Eddie Adler owned the

store. Frank Elau was his assistant. Many years later

Frank was to be the manager and it would be owned by Audio Exchange.

I later purchased a Pentron

9T-3C two speed machine and it cost $119. This handled 7" reels and had

speeds of 3-3/4 and 7-1/2 ips. I bought it at High

Fidelity Centre near the Pix theater in White Plains. Eddie Adler owned the

store. Frank Elau was his assistant. Many years later

Frank was to be the manager and it would be owned by Audio Exchange.

Scarsdale was only 20 miles from New York City. I was in high school and my friends and I often took the train in to Grand Central Station and then the subway downtown to Cortland Street. This was known as "Radio Row" that had all kinds of stores with radio, hi-fi, and war surplus of many different items. Leotone had thousands of tubes guaranteed to light. Hudson Radio had some of the more recent hi-fi equipment. We also visited Harvey Radio and Lafayette Radio stores. We found war surplus Gibson Girl emergency transmitters complete with hand crank and parachute for only $3.95. We found they broadcast in the AM band and we tried to reach each other's houses with them.

![]()

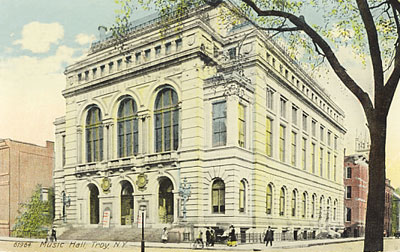

After graduating from Scarsdale High School in 1954, I went to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, NY. I started out in chemical engineering but changed over to electrical engineering later in my freshman year. Troy was a very old town and RPI had been established there in 1823.

While at RPI, I attended concerts at the Troy Savings Bank Music Hall. This picture was taken by Stanley Blanchard and published in Industrial Photography magazine, June 1986. No supplementary lighting was used for this award winning-picture as it was taken during a performance. Recent performers include Ella Fitzgerald, Dave Brubeck, Carlos Montoya, Isaac Stern, Yo Yo Ma, Sonny Rollins and many other great musicians.

The Troy

Savings Bank Music Hall, located in downtown Troy, NY, is owned by the Troy

Savings Bank and is operated by a not-for-profit organization. Architecturally

and acoustically, the Music Hall is renowned as one of the finest halls in the

world. Founded in 1823, the Troy Savings Bank operated from smaller banking

offices until, in 1870, the board of directors decided to move its offices to a

new location one block away at 7 State Street. To demonstrate the bank’s

appreciation for many years of patronage by the local citizens, the plans for a

new building included a music hall on the upper floor. The grand opening was

April 19, 1875. The seating capacity was 1,253 and seating arrangements have

never been changed. The narrow seats were built for smaller people with

under-the-seat racks for top hat storage. The post card at the left shows the

music hall and was sent from Troy on July 9, 1915.

The Troy

Savings Bank Music Hall, located in downtown Troy, NY, is owned by the Troy

Savings Bank and is operated by a not-for-profit organization. Architecturally

and acoustically, the Music Hall is renowned as one of the finest halls in the

world. Founded in 1823, the Troy Savings Bank operated from smaller banking

offices until, in 1870, the board of directors decided to move its offices to a

new location one block away at 7 State Street. To demonstrate the bank’s

appreciation for many years of patronage by the local citizens, the plans for a

new building included a music hall on the upper floor. The grand opening was

April 19, 1875. The seating capacity was 1,253 and seating arrangements have

never been changed. The narrow seats were built for smaller people with

under-the-seat racks for top hat storage. The post card at the left shows the

music hall and was sent from Troy on July 9, 1915.

Attendance was not only by local citizens and visitors but also by students from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Russell Sage College and others from the surrounding area.

![]()

I took the Pentron recorder with me to RPI for my freshman year and used the amplifier section and speaker to play FM from the old Pilot fm tuner that my father was no longer using. I added a switch to the recorder so that I could run just the amplifier without the motor running all the time. WQXR had a relay station, WFLY, in the Troy area so I could still listen to classical music on my favorite station.

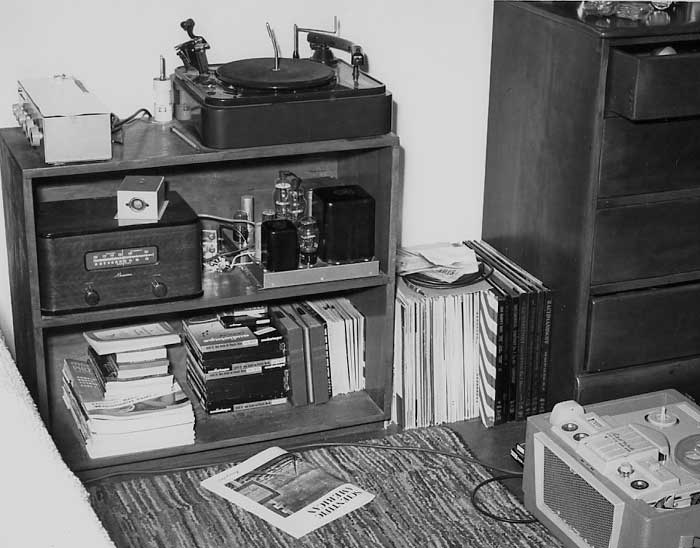

This was my bedroom system in 1955. The Garrard changer is at the top center. The Revere T-700-D recorder is on the floor at the right. I borrowed this from my father since my Pentron was at RPI. I also had some 78's, LP's and 45 rpm records. A few reels of tape are in the cabinet.. The tuning eye is on the top of the Meissner tuner. The Heath WA-P2 preamp at the upper left faces the bed.

During my freshman year I was very impressed with Pete

Morton's hi-fi system. It was a Bogen DB20 amplifier

and an Electro-Voice SP12 speaker in an EV Aristocrat enclosure. Pete often

played Dvorak's 5th symphony "The New World" which I could hear from

way down the hallway.

During my freshman year I was very impressed with Pete

Morton's hi-fi system. It was a Bogen DB20 amplifier

and an Electro-Voice SP12 speaker in an EV Aristocrat enclosure. Pete often

played Dvorak's 5th symphony "The New World" which I could hear from

way down the hallway.

I learned from Frank Borden and George Benson, other

freshman hi-fi enthusiasts, that the Aristocrat, Regency and other cabinets

could be custom made by a carpenter on campus. I have an unfinished Aristocrat

made for $25 and bought an Electro-Voice SP12. This was a higher power version

of the SP12B with a larger magnet and a supplementary whizzer cone. I then use

this at home in the corner of my bedroom as it was a rear loaded corner

cabinet.

I learned from Frank Borden and George Benson, other

freshman hi-fi enthusiasts, that the Aristocrat, Regency and other cabinets

could be custom made by a carpenter on campus. I have an unfinished Aristocrat

made for $25 and bought an Electro-Voice SP12. This was a higher power version

of the SP12B with a larger magnet and a supplementary whizzer cone. I then use

this at home in the corner of my bedroom as it was a rear loaded corner

cabinet.

|

|

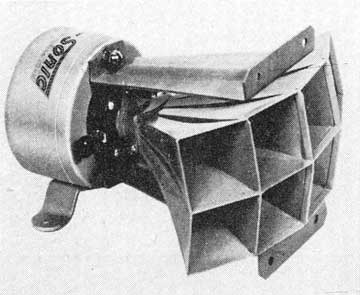

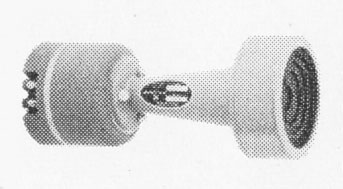

“ULTRA-SONIC TWEETER. Frequencies extending from 5000 cps well into the ultrasonic range are reproduced by the new Stephens Model 214 tweeter. Designed to improve fidelity of reproduction from high-quality source material, the 214 assembly includes a 2 x 4 multi-cellular horn. Installation is facilitated by insulated spring-type binding posts. Stephens Manufacturing Corporation, 8538 Warner Drive, Culver City, Calif.”

|

Despite the whizzer, there just weren't enough highs and later I add a Stevens model 214 horn tweeter which sat on top of the cabinet with a 5kc crossover network that I made.

|

|

I later bought an Altec 601A coaxial 12" speaker to use in it. I found the aristocrat didn't have much deep bass so I built a large bass reflex cabinet for the Altec. It helped some.

|

|

In the early 1950's, the Audio Fair was sponsored by the Audio Engineering Society in conjunction with its annual fall meeting and convention. It was on the fifth and sixth floors of the Hotel New Yorker, in New York City. Admission was free to all exhibits. The shows typically ran for four days, Wednesday through Sunday. I went almost every year. At the 1954 show, I was most impressed with the sound of the Brociner Model 4 speaker system in the Tetrad Diamond demonstration room. |

|

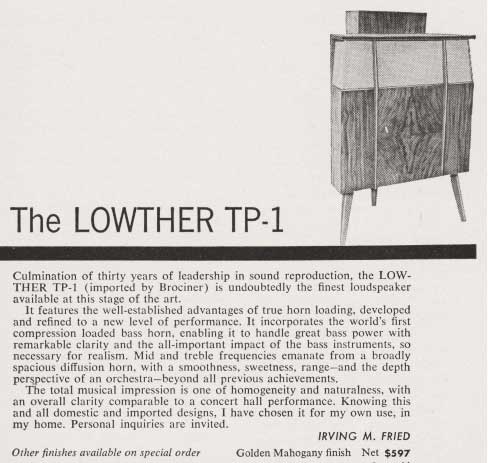

Brociner Model 4 and Lowther TP-1 Speaker

|

|

“CORNER SPEAKER The Model 4 horn is the newest in the series of high-quality loudspeakers manufactured by Brociner Electronics Laboratory, 1546 Second Ave., New York 28, N. Y. Unique in many respects, the Model 4 utilizes two horns, the smaller of which has its mouth at the grille at the upper portion of the enclosure, and covers frequencies from 150 to 20,000 cps. The range below 150 cps is derived from the back of the driver unit, through a folded horn whose mouth is directly below the speaker structure. This arrangement not only utilizes the space below the cabinet itself as an effective part of the speaker system but also uses the walls of the room as an extension of the folded horn. The driver unit is a twin-cone speaker with a field magnet producing 20,000 gauss. A 6-in. cone, capable of great excursion, covers the bass and middle register. A second, smaller cone, working through a mechanical crossover, covers the higher frequencies.” |

The system was actually designed and built by

Lowther of England and was similar to the TP-1 speaker system. Even at high

levels, it was smooth and clean compared to other speakers at the show. Another

unique feature of this system was that a single driver covered the entire

frequency range and no crossover networks were involved. Victor Brociner later discontinued his business and went to work

for University Loudspeakers in White Plains. Many years later he founded Avid

loudspeakers in Rhode Island. Victor told me many years later that,

confidentially, working at University was nothing but an ulcer factory.

Advertised

in the September 1956 issue of High Fidelity magazine

![]()

As far back as the late 1940's, when I was in grade school, I had been fascinated with my reactions to sounds. I found that I could hold down individual keys of my grandmother's piano and listen to the sound decay. The highest notes had the most interesting effects of spaciousness. I became fascinated by effects such as reverberation or time delay but in a separate channel, to give an added 3-D sense of being engulfed in sound. In the mid 1950's, before stereo was available, I experimented with delay lines that added a dimension to the monophonic sound with a delay by using a second speaker located in a different place than the main speaker. I used a disc recording head for cutting records coupled with a spring, rubber band, etc. to a phonograph cartridge and use the output of the cartridge as a source for a second channel with a different speaker location. I found additional channels could have different delay times and each could have a different speaker location.

There were commercial devices available later that accomplished similar effects. There was the X-Ophonic system that had a small speaker at one end of a coiled tube and a microphone at the other end. The delayed output was used as a second channel. Fisher had the Space Expander that used springs and a pickup. In France there was an auditorium that was used by Varese that had speakers placed in continuous lines all around the ceiling that were switched in sequence to give the effect of the sound traveling all around the audience. Clearly, there had been interest similar to mine to accomplish a better sonic illusion.

When Emory Cook came out with binaural records, I bought an adapter for my tone arm and two GE RPX-050 cartridges to play them. Emory and Rudy Bozak had an impressive sound at the NY hi-fi show. Emory had some great binaural recordings like Sounds of the Sea, Nightmare in the Mosque, Speed the Parting Guest and many others. He had a great sense of humor that was evident in his publication, The Audio Bucket. When AM-FM binaural broadcasts were introduced by WQXR in New York City, I was listening to them on my father's National Criterion binaural tuner.

In 1957 I spent some time talking with Paul Klipsch at the hi-fi show about his method of deriving a center channel from the left and right channels. He used a McIntosh amplifier that had a floating ground. He connected the center speaker between the two 4 ohm terminals of the stereo amplifier. I was concerned that if equal signals were present and out of phase with each other with this connection, no output would be heard on the center channel. He already had a demonstration set up and I was not able to hear any differences on a stereo recording.

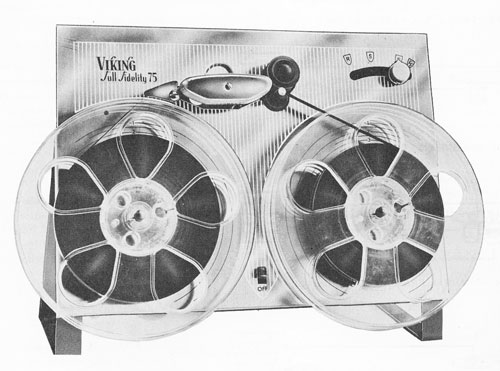

Finally, stereo tape recorders became available at a reasonable price, I bought a Viking FF75 deck with a stacked Dynamu head. I also bought an RP60 record-play preamp and two Telefunken M-410 dynamic microphones. In December I bought parts from Viking to build a second RP preamp. The preamps were tube type and used a green magic eye tube as a record level indicator. I made a copy of the Viking carrying case for the deck and preamps. It was made of plywood and I covered it with a textured wall paper.

In October 1957, I bought a Garrard 301 turntable and Pickering 190D tonearm from Leo at the Troy Camera Shop. This replaced my Garrard changer.

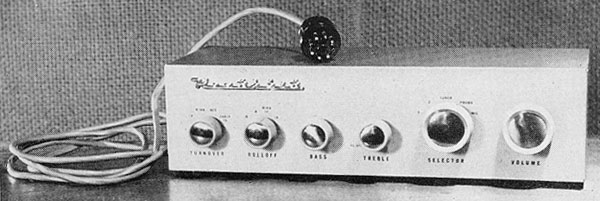

About 1958, I purchased a Heath SP-2A stereo preamp with a balance control on a remote wire. It sold for $56.95. I bought two Acrosound output transformers from Radio Shack and built two 25-watt amplifiers to use for stereo. My parents let me use the living room for a while to play this stereo system.

I also bought a Revere T-11 recorder. This was like my fathers T-700-D but mounted in a 19" rack and handled 10-1/2" reels. I converted this to 1/2 track stereo with a Revere kit so I could play 1/2 track stereo tapes. It recorded only mono, though.

On February 22, 1960 I traded in the Pickering arm and bought an ESL 1000 arm from Audio Exchange. This arm had interchangeable cartridge shells so that I could use one shell for the Cook binaural adapter and another shell for the Shure M3D cartridge. The arm had a spring adjustment for tracking pressure. In the unlikely event that the turntable was upside down, the correct tracking pressure was still available. This was demonstrated at one of the Hi-Fi shows. I don't know what held the record to the turntable. Don Smith, a friend and hi-fi enthusiast who was doing record reviews for the Reporter Dispatch newspaper in Westchester County, gave me a Shure Studio Dynetic arm and cartridge.

About this time, I purchased a Revere T-11 recorder. The T-11 was a half track mono machine. However, an in-line stereo head kit was available from Revere. I installed this and was able to play stereo tapes. The second channel was a high impedance and had to be run directly to a tape head preamplifier but that was no problem. The T-11 sold for $284.50 and the stereo kit was $34.50.

It was during this time that I became an enthusiast of

JBL. The systems were very modern looking and the drivers also had a nice

appearance. The literature was very convincing as well.

It was during this time that I became an enthusiast of

JBL. The systems were very modern looking and the drivers also had a nice

appearance. The literature was very convincing as well.

I bought the plans for the C40 Harkness folded horn

system and proceeded to construct a system. This had a 175DLH horn and lens

assembly. This driver was very impressive to look at. The acoustic lens at the

front of the horn was a series of perforated steel plates. The plates had a

hole in the center which was progressively larger toward the front. This formed

the lens. Sound was delayed more at the edges than at the center, creating a

more spherical wave front. I measured response out to 15 kHz for this driver.

I bought the plans for the C40 Harkness folded horn

system and proceeded to construct a system. This had a 175DLH horn and lens

assembly. This driver was very impressive to look at. The acoustic lens at the

front of the horn was a series of perforated steel plates. The plates had a

hole in the center which was progressively larger toward the front. This formed

the lens. Sound was delayed more at the edges than at the center, creating a

more spherical wave front. I measured response out to 15 kHz for this driver.

The 15" woofer I used was a model D130A driver.

This was the one with the paper dust cap over the 4” voice coil. It was

different from the D130 shown at the left, which had an aluminum dust cover.

The paper cover did not extend the highs as it did with the aluminum cover. The

aluminum cover would have otherwise extended output into the 175DLH frequency

range and caused interference. The N1200 crossover was used for a crossover

frequency of 1200 Hz.

The 15" woofer I used was a model D130A driver.

This was the one with the paper dust cap over the 4” voice coil. It was

different from the D130 shown at the left, which had an aluminum dust cover.

The paper cover did not extend the highs as it did with the aluminum cover. The

aluminum cover would have otherwise extended output into the 175DLH frequency

range and caused interference. The N1200 crossover was used for a crossover

frequency of 1200 Hz.

It was a lot of work cutting the wood and fitting all the pieces together. The system was very heavy when it was all finished. The sound was nice, but there was no bass to speak of and no deep bass at all. It would play very loud and close listening was not pleasant. I only made one of these. In order to play stereo, I had to borrow my father’s Altec 604C coaxial speaker that was in a large bass reflex cabinet

![]()

After I graduated from RPI in June of 1959, I had applied for a job at University Loudspeakers at 80 South Kensico Ave, White Plains, NY, but they were not hiring. It was only 4 miles from my home in Scarsdale. I finally found a job at the Sonotone Corporation in Elmsford, NY through an employment agency in White Plains. It was only a couple of miles further away. Although the main Sonotone product was hearing aids, they also made vacuum tubes, nickel-cadmium batteries, phonograph cartridges, microphones, tape heads and speakers. The job was in the phono cartridge department. My first project was to set up a listening room and equipment for evaluating cartridges. About this time I bought a Heath oscilloscope and Audio generator to use at home.

I continued to attend concerts, this time at Carnegie Hall in New York City. I was usually able to get a seat in the third or fourth row. I also went to concerts at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY. At the hi-fi shows I enjoyed doing booth duty at the Sonotone exhibit. I was able to meet many potential customers and learn their interests. I got to see the shows as well. I also attend many Audio Engineering Society meetings when they were held in New York City.

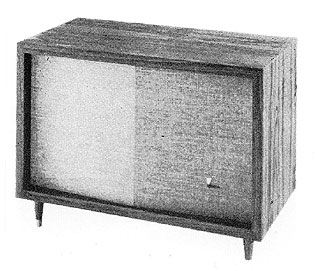

After using the JBL system for a while, I decided to

pursue my first impression of the Brociner Model 4

using the Lowther drivers that I heard at the New York Hi-Fi show. Although the

system was only playing mono, it sounded very clean and smooth. At this time

Harman-Kardon was marketing the Citation X speaker

system. The drivers were modified Lowther PM-6 drivers with a canoe shaped

whizzer and a few pieces of aluminum foil glued to the main cone. The whizzer

covered the range from 2 kHz to 7 kHz. The drivers faced upwards and had a

plaster mushroom shaped stabilizer that provided horn loading at higher

frequencies. The rear of the cone was coupled to a split, slot-loaded conical

horn. Each folded section was 7-1/2 feet long. The slot at the end of the horn

was said to reduce phase shift within the horn. Corner placement was not

necessary. The enclosures were 20” wide, 14-3/4” deep and 36-1/2” high. This

picture from a magazine advertisement is not exactly like the actual system but

seems to be only an artist rendition.

After using the JBL system for a while, I decided to

pursue my first impression of the Brociner Model 4

using the Lowther drivers that I heard at the New York Hi-Fi show. Although the

system was only playing mono, it sounded very clean and smooth. At this time

Harman-Kardon was marketing the Citation X speaker

system. The drivers were modified Lowther PM-6 drivers with a canoe shaped

whizzer and a few pieces of aluminum foil glued to the main cone. The whizzer

covered the range from 2 kHz to 7 kHz. The drivers faced upwards and had a

plaster mushroom shaped stabilizer that provided horn loading at higher

frequencies. The rear of the cone was coupled to a split, slot-loaded conical

horn. Each folded section was 7-1/2 feet long. The slot at the end of the horn

was said to reduce phase shift within the horn. Corner placement was not

necessary. The enclosures were 20” wide, 14-3/4” deep and 36-1/2” high. This

picture from a magazine advertisement is not exactly like the actual system but

seems to be only an artist rendition.

I traded in the JBL C40 towards the Citations. The Citations were nice, but they didn't handle any deep bass. The Lowther drivers soon developed rubbing voice coils. The surrounds and spider centering material were flat closed-pore urethane foam that didn’t keep the voice coil centered very well. The coil gap was extremely small and provided 17,500 gauss flux density. The magnet was made of Ticonal G, which was very strong. I took the drivers down to Harman-Kardon in Plainview, Long Island and Leon Kuby replaced them for me with thin rubber surround versions. This eliminated the rubbing, but they still didn't handle any power at low frequencies.

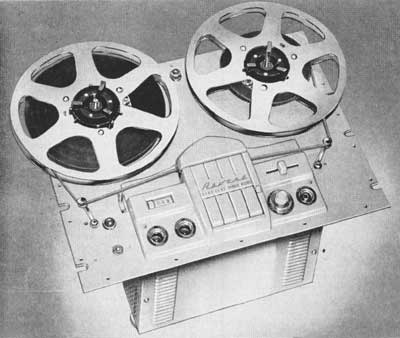

In May I was required to be on active duty for 6

months at Ft. Monmouth, NJ. In September 1960 I assembled a Harman-Kardon Citation 1 preamp kit while working at the Ft.

Monmouth Signal Labs. I also made my most expensive purchase, a Magnecord 728-44 stereo tape recorder. It was $995.00 less

a small trade-in for my Revere T-11. The Magnecord

recorded at 7-1/2 & 15ips in half track and also played 1/4 track stereo.

It handled up to 10-1/2" reels. The quality was excellent.

In May I was required to be on active duty for 6

months at Ft. Monmouth, NJ. In September 1960 I assembled a Harman-Kardon Citation 1 preamp kit while working at the Ft.

Monmouth Signal Labs. I also made my most expensive purchase, a Magnecord 728-44 stereo tape recorder. It was $995.00 less

a small trade-in for my Revere T-11. The Magnecord

recorded at 7-1/2 & 15ips in half track and also played 1/4 track stereo.

It handled up to 10-1/2" reels. The quality was excellent.

At the end of 1960 and after returning to Sonotone, I bought a Citation III tuner kit. This replaced

my Scott 314 tuner. It worked well but didn’t have the quieting that I

expected. In May, 1961 I was married and we lived in an apartment in White

Plains. To improve reception there, I bought a large 17-element antenna and

Alliance rotator for better TV and FM reception. I was able to mount it in the

attic above the apartment and run the wires through the ceiling

At the end of 1960 and after returning to Sonotone, I bought a Citation III tuner kit. This replaced

my Scott 314 tuner. It worked well but didn’t have the quieting that I

expected. In May, 1961 I was married and we lived in an apartment in White

Plains. To improve reception there, I bought a large 17-element antenna and

Alliance rotator for better TV and FM reception. I was able to mount it in the

attic above the apartment and run the wires through the ceiling

I was able to bring the Citation X into the lab at Sonotone and verify that the response was indeed very smooth over much of the high end. I used pink noise, a General Radio 1554 Sound and Vibration analyzer and an Altec 21D microphone system to measure it. When I spoke to Stu Hegeman at Harman-Kardon about response that was a little rough at 250Hz, he admitted he hadn't made very many measurements on the system and asked me if I would like to make some more tests. I told him I would like to. He said he would get back to me about the tests, but I never heard from him.

About 1962, I decided it was time to make a better

system. I rented a pair of AR3's from Boynton-Goodall in Eastchester, NY. I was

very impressed with the bass performance of the AR woofers that had good

response to 45 hZ and very low distortion. At this time I was working with Phil Kantrowitz

at Sonotone in evaluating distortion in high

frequency drivers. We found the AR tweeters had the lowest distortion and

smoothest response. However, I found the mid-range to be lacking. I decided to

build a system incorporating the AR woofer and tweeter but with a Lowther PM4

driver with the Citation X mushroom stabilizer as the mid-range. This would

disperse the mid frequencies over a wide angle. The tweeter radiated a wide

angle and extended response to 20 kHz.

About 1962, I decided it was time to make a better

system. I rented a pair of AR3's from Boynton-Goodall in Eastchester, NY. I was

very impressed with the bass performance of the AR woofers that had good

response to 45 hZ and very low distortion. At this time I was working with Phil Kantrowitz

at Sonotone in evaluating distortion in high

frequency drivers. We found the AR tweeters had the lowest distortion and

smoothest response. However, I found the mid-range to be lacking. I decided to

build a system incorporating the AR woofer and tweeter but with a Lowther PM4

driver with the Citation X mushroom stabilizer as the mid-range. This would

disperse the mid frequencies over a wide angle. The tweeter radiated a wide

angle and extended response to 20 kHz.

I made arrangements with Ed Villchur to purchase two 5/8" excursion woofers and drove to 24 Thorndike Street in Cambridge, Boston to pick them up. I visited with Ed for a short time while I was there. Ed was pleased that we had found the AR tweeters to have the lowest distortion of all the tweeters we had tested. I used the tweeters we had previously purchased from Ed for the tweeters in my system.

I designed the enclosure for the woofer portion to have the same volume as that used in the AR3 system. I had two cabinets with walnut veneer constructed by a cabinetmaker and later made the grilles myself.. I weighed out the fiberglass and packed it the same as the AR3.

In May 1962, I imported Lowther PM4 drivers directly from Donald Chave at Lowther in England. Flux density for the PM4 was 22,000 gauss, about the strongest magnetic gap ever used for a speaker. This design followed the original design of Paul Voigt. The PM4 drivers came with a short stabilizer, However, I decided to purchase two mushrooms from Harman-Kardon. By then, they had changed them from plaster, which was used in the Citation X, to styrofoam. I didn't know if this would be as good because the shape had changed slightly but I decided to use them anyway.

The grille on top would cover the front, sides and top. I made a frame that would fit over the posts and back. I then covered it with an open weave plastic cloth. I used a piece of felt on the back that would absorb reflections from sound radiated to the rear. This was a similar arrangement as the Citation X system that used a piece of fiberglass for that purpose. I also filled the enclosure portion for the PM4 driver with fiberglass.

I sealed around the edges of the PM4 driver with Mortite. Connections for the system went to dual banana plugs at the back of the top section.

There was such a difference in efficiency between the AR woofer and the Lowther PM4, I decide to use an electronic crossover to drive each speaker. To get the proper response, I used passive UTC butterworth bandpass filters that roll off at 60dB/octave at 250Hz. I made two 60 watt amplifiers using Acrosound T-330 output transformers and EL34 output tubes. These were used to drive the woofers and are on the upper shelf in the open compartment. To drive the Lowthers as mids, I copied the Marantz 8B amplifier. I was able to purchase the power and output transformers directly from Marantz and borrowed the Marantz 8B amplifier used by Sonotone to copy the layout. This is on the bottom shelf at the left. I made two tweeter 20-watt amplifiers on a single chassis to drive the tweeters using EL84's and small coupling capacitors to roll off the low end. This is on the bottom shelf at the right. On the upper shelf at the right is an ultrasonic remote control unit.

In the left side of the cabinet is the Harman Kardon Citation III stereo FM tuner and below it is the Citation I preamplifier. At the left on the top of the cabinet is the Alliance antenna rotator for the 17 element FM antenna in the attic.

I made a special equipment cabinet, styled after the JBL C40 to house all of this equipment. This included a lift-up top for the record player. The amplifiers were normally hidden by an insert covered with grille cloth to allow ventilation. The cabinet was stained in walnut and several coats of varnish made it easy to clean.

The record player portion contained a Garrard 301 turntable, ESL arm with plug-in shells and a Shure Dynetic arm-cartridge combination that Don Smith had given me. The whole assembly was mounted on springs to give vibration isolation. The lift top could be left in any position with a special hinge. I used a damp photo sponge and water to clean the dust from the records. This can be seen in the upper left with the plastic container of water.

The whole system became sort of complicated but sounded very impressive. You can imagine with all of the tubes in the cabinet, the heat became significant. I used a Rotron muffin fan to blow on the tuner and preamp. I had a second fan to blow across the power amplifiers. This ventilation kept everything reasonably cool even in the apartment in the summer months.

All this equipment was constructed without my being able to make very many measurements. Having been exposed to good test equipment at Sonotone, I decided it was time to replace my inaccurate Heath Oscilloscope with an accurate one. On November 28, 1961 I bought a Hewlett-Packard 122B dual trace scope for $600 so that I could look at the left and right channels at the same time. I made a cart for it with some electrical conduit that was bent for me by the maintenance people at Sonotone.

I also assembled an Eico 250 AC Voltmeter and a 666 tube checker so that I could do more accurate measurements at home. I checked the voltmeter against the Ballantine AC voltmeter in the lab and found it was reasonably accurate. In November 1962 I started assembling a Schober organ kit.

We moved from the apartment to a new house in Brewster, NY. on June 1963. It had a large living room that finally did justice to my tri-amplified speakers and I could play them as loud as I liked. The Citation III tuner was not able to pick up stations in stereo as well as I would like, even with the 17-element antenna and rotator in the attic. Brewster was about 50 miles north of New York City. I decided to trade in for a McIntosh MR65B tuner which worked much better. Right after I bought the MR65B, the MR71 came out. I wrote to Morris Painchaud at McIntosh and explained that I really wanted the best tuner and could I swap? As several customers who had recently purchased MR65B's had already requested this, he agreed to a swap plus a charge of $120.00 for the MR71. This tuner worked very well in stereo.

The Magnecord 728 had soft recording heads that were made by Magnecord. Head wear was becoming very obvious. In March 1966, I decided to trade the Magnecord 728 in towards a Magnecord 1024. It had heads that were made by Nortronics and were much less affected by wear.

![]()

I made several live stereo recordings with the Viking stereo recorder and the Telefunken dynamic microphones. On June 8, 1958 I made a second recording of Harvey Bourez, my mother's organ teacher, playing the big Wurlitzer organ at the Leows Theater in New Rochelle. The manager of the theater let us use the organ early Sunday mornings before the theater opened for the first show. The organ was in need of repair and was a little slow to respond, but for the fantastic sound and experience in making the recordings, it was well worth while.

Later, when I bought the Magnecord 728, I was able to make even higher quality live stereo recordings. One is of diesel engines at the Harman, NY train station on November 25, 1961. I was able to borrow a power converter from ATM to provide power conversion from ten 60-amp Sonotone nicad batteries. The recorder sat in the back of my Volkswagen and the microphones were spaced about 20 feet apart along the bank overlooking the tracks. Several trains arrived and departed, including a big diesel engine that shook the car. Later on, I was able to shake the apartment with the recording.

On January 21, 1962, I traveled to Springfield, MA with my friend Ed Lessing, who also worked at Sonotone, to make a recording at a small concert. His father, Nardus Lessing, played the cello and was accompanied by pianist Betty Maybe. I recorded the entire performance in half track at 15 ips and made tape copies for him. Another session on October 4, 1963 was of Lilla St. John, a friend of Ernie Briggs at Sonotone. She played many piano pieces in a studio that would be used for her promotional material. I also recorded the Mount Union College Choir at a church in Brewster, NY on March 25, 1964.

Night sounds always fascinated me and I recorded these complete with katydids as well as thunderstorms and wind blowing ice from the trees during the winter. With a portable stereo recorder that I bought, I recorded many street sounds, the lab at Sonotone and my friend Dimitri who played the bagpipes on the Sonotone grounds during lunch break.

Later, I bought an Advent stereo cassette recorder with Dolby noise reduction. I recorded many concerts of the Binghamton Symphony when they were still playing in the West Junior High School auditorium. I set up the microphones about 12 feet apart at the edge of the balcony. The first recordings were with the Telefunken M-410 dynamic mics, but later I use Bruel & Kjaer 4133 mics. One of the other engineers at McIntosh, Ron Evans became interested in recording there also. By this time we knew which circuit breaker in the stage power panel turned the power on for the balcony outlets.

![]()

In January 1963 I started work on my first magazine article about a volume expander-compressor. I was very interested in restoring dynamic range to recordings that seem very lifeless. At that time Fairchild had a "Compandor" that used neon lights to control the amplifier input level. They had a characteristic on or off behavior that was very noticeable. My slower acting incandescent lamp circuit with driver transistor and photocell worked much better. It was titled Build a Hi-Fi Volume Compresser-Expander. It was published in Popular Electronics on October 1964. It was later reissued in the Electronic Experimenter's Handbook for the fall of 1965

![]()

In 1959 I made my first car audio system. It was in my first car, a Volkswagen beetle. FM radios were not available for cars yet, but I was anxious to listen to good sound in my car. I built a small Heath FM tuner and mounted it under the dash. I used a separate chassis for a vibrator power supply and amplifier and put that under the front hood. The VW had a 6-volt battery system so there was no problem for filament voltages.

I was able to find an EMI elliptical woofer about 9" X 14" and build a 2 cubic foot enclosure that fit behind the back seat of the VW. I used an Electro-Voice T35 tweeter with a level control for the highs. The sound bounced off the angled back window very nicely and the system sounded very good. The Heath tuner performed only fair with the car antenna. The next year Blaupunkt came out with a hybrid AM-FM car radio. It was tubes except for the power amplifier and oscillator power supply for the high voltages. I installed this in place of the Heath and reception was greatly improved. The sound was able to shake the VW.

![]()

Additional Equipment

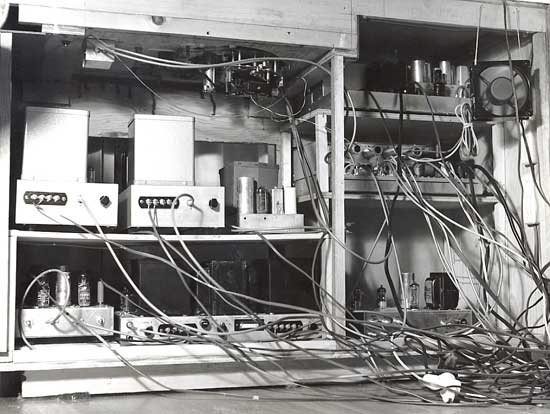

This is some of the equipment I was using around 1965. At the Sonotone employee auctions, I was able to purchase two of the Berlant 30 tape decks for $35 that had been used for production testing of tape heads. I was able to borrow a Berlant record-play amplifier from Sonotone and with help of the metal shop, was able to make the metal parts for four record/play amplifiers. I was able to purchase the bias oscillator coils from Concertone and made four complete record/play amplifiers. I also had also been able to buy the 6-foot relay racks that the decks had been mounted in. In the center are the four record-play amplifiers and a General Radio 913 beat frequency audio oscillator. At the right are my McIntosh MR71 tuner, Citation 1 preamplifier and Magnecord 1024 1/4 track tape recorder.

![]()

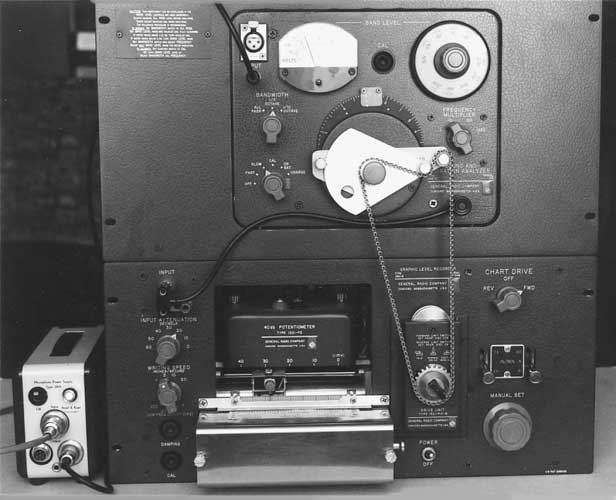

When I began work at McIntosh in March of 1967, I was still using the tri-amped speaker system. In 1968, I was able to purchase a complete set of test equipment for home including a demo General Radio 1564 Sound and Vibration Analyzer (top), and 1521B graphic Level Recorder (bottom). The analyzer could be driven automatically through a chain by the chart recorder. Chart paper was then driven by the recorder and a pen plotted the response. I used this for acoustic measurements. I also purchased a used Bruel & Kjaer 2801 microphone power supply (left), a 1/2" 4133 microphone and a new 2619 FET preamp. I had also bought a Scott random noise generator to be used with the sound and vibration analyzer.

I was still using the Eico 250 AC voltmeter and GR 913 beat frequency oscillator. The oscillator could also be chain coupled and driven by the chart recorder. Chart paper was then driven by the recorder and a pen plotted the response. I used this for impedance measurements. Later, I replaced the GR 913 oscillator with a newer GR 1304B oscillator that was easier to use and could also be driven with the chart recorder. This was a dream come true. Now I could make accurate acoustic measurements at home and see what was really going on with my system. This equipment was as what I was using at the lab.

I found the response of my system was not as smooth as I had wanted to believe. Also, when sweeping the Lowther PM4 with a sine wave, there were many harmonics and buzzes that could be easily heard. It was time to begin a new search towards perfection. This was an ideal time because my work at McIntosh was to develop a line of systems and I could pursue my interest in the development of new and better systems for the lab as well as for myself. I also used this equipment to write an article for Audio Amateur titled “Loudspeaker Evaluation: Ear or Machine” and was published in two parts in the 1/75 and 2/75 issues.

Although I had been mainly concerned with classical music most of my life, many McIntosh customers were into rock music. The energy spectrum of rock music is different and placed new demands on the speaker power handling requirements. As a result, some of my listening evaluations included rock music. In the 70's, artists such as Edgar Winter, Rick Wakeman, Pink Floyd and Alan Parsons became a regular part of my experience in sound. I used The Dark Side of the Moon to demonstrate the advantages of the ML-1C loudspeaker because it could reproduce the 25Hz heartbeat. When we moved to the new acoustics lab at plant 4 in 1979, I was one of the first customers in Binghamton to get a copy of Pink Floyd's The Wall at Discount Records when it first arrived by Greyhound bus. Later, my collection of rock music expanded, as the sounds became more and more interesting.

![]()

Early in my adventures, I found that a total sonic experience requires total darkness. At one time in the late 50's, I had built a 3-channel color organ that divided the audio frequency spectrum of music, or whatever I played on my hi-fi, into three different frequency bands. I used thyratron tubes to control three 150 watt spotlights that projected the three basic colors. Red was for lows, green for mids and blue for highs. When projected onto a wall or some other object, the three colors would blend to form the other colors as well. The colors and patterns constantly changed in rhythm to the music. Although it made a fascinating display, it only took away from the listening experience. Total darkness, on the other hand, frees the mind to concentrate purely on the sound. Visual distractions of any kind limit our reactions and the inner experience of our imagination.

Stereo was nice and added a much needed dimension, but it wasn't nearly enough for me. When four channels appeared in the 1970's, I obtained a four-channel recorder and was further impressed with the demo tapes. However, tape hiss was a major problem for 4 channels. Performance of the four channel records was limited by response and separation problems. The method of microphone placement for these recordings offered no vertical dimension. An article in Hi-Fi News on tetrahedral stereo looked more promising where one speaker was located in the ceiling and three others were located on the plane of the floor in a triangle. Unfortunately this concept never caught on. When visiting MIT, I remember Mark Davis showing Sidney Corderman and I a four-channel microphone configuration that would cover a solid angle of 360 degrees, but again nothing came of it. Four-channel sound had failed as a consumer item, mostly due to poor technology. Later, the Calrec microphone system appeared, but by then the 4-channel medium was dead.

![]()

Meanwhile, Something Else Was Happening

While high fidelity was struggling to make improvements, something else was happening. Ever since seeing the movie "Spellbound", when it first came out, I had been much taken with the new eerie sound used in the dream sequences. I later learned this was done with a Theremin, the first electronic instrument. It operates using a beat frequency oscillator and body capacitance. Bringing one hand close to one antenna varies the volume and bringing the other hand closer to other antenna increases the audio frequency. Vibrato can be achieved by rapidly rotating the hand at the frequency antenna. I found the plans to build one in Radio-TV News back in the 50's, but could never get it to work as well as what I had heard.

I had also become fascinated with electronic music because it opened up a much wider range of sounds to the composer. I was able to hear the music of Badings, Stockhausen and Varese. I learned that several compositions had been made for multiple channels, but I had no way of getting or playing them. I was also taken with the sound track to Forbidden Planet composed by Louis and Bebe Baron. They also composed the sound for the movie Atlantis. I attended the paper they presented at the Audio Engineering Society in the early 60's describing how they composed their music.

Use of an orchestra or other conventional instruments has produced some excellent and moving sounds. The sound of each instrument can be easily recognized by the characteristic array of harmonics that it creates. In electronic music, there is literally an infinite number of different "instrument sounds". In fact, the potential of electronic music implies that there is no limit to the possibilities except the imagination of the composer. Recent technology now provides the means to synthesize sound for newer and deeper emotional experiences that we have never encountered before. It was the beginning of my dream for new experiences in sound.

What's interesting about this new medium is that some music is never played in a concert hall at all. It goes directly from mixing console to CD and is only heard by the composer or final mixer through headphones or a monitor speaker. There are no live performances or real instruments to compare the sound with. The new sound of popular and new age music is often enhanced with excellent electronic depth and spaciousness that is very appealing. I'm not talking about reverb devices that used bucket brigade chips like those used in the Sound Concepts SD-50. This is more random. The newer technology first appeared back in the late 1970's and is an excellent example of sound that can stimulate the pleasure centers in the brain. Its use is now widespread. Some New Age music is just plain hypnotic and is what I was looking for when I was in my teens.

![]()

The quest for higher fidelity has brought us, the consumer, beyond the world of limited bandwidth, limited dynamic range and the monophonic sound of the Victrola and early radio receivers. Now we can feel the subsonic 64 foot organ pipes and hear all the triangle and cymbal harmonics. It took us from the noise of record grooves, turntable rumble, tape hiss, overmodulation, clipping amplifiers and distorted speakers all the way to a new world of dynamics, clean full range sound and multiple channels. Despite all of these improvements, high fidelity still has a long way to go to perfection. It may never go further now because today's program material has changed. Hi-Fi has been replaced by new words and meanings like Stereo, Home Theater and Car Audio. Stereo is still limited in part by recording methods, speakers and room acoustics. Binaural recording and headphone playback eliminate the effects of the speaker and room but lacks the body perception of high level sound and lower frequencies as well as the freedom of turning the head to localize sounds.

Home theater sound is designed for emotional impact and accuracy is not a prime concern. Sound effects and subwoofers are the big features. It has yet, if ever, to become true multi-channel stereo with any accuracy compared to the real world. However, it is really only designed to effectively complement the movies. Stereo in the car can sometimes be made very pleasing but often very loud and creates its own little world. Accuracy is not possible in a car environment and loud sound with deafening bass has become more of a status symbol and an annoyance to others. Both home theater and car sound are often played at excessive levels. Movies in theaters and other entertainment places play the sound at punishing levels. I call this “sledge hammer sound.” See my page about listening and hearing.

Live classical concerts are now electronically enhanced with microphones and speakers. The goal of reproducing home sound as accurately as possible to a live performance is losing its meaning for most consumers. Finding a non-enhanced live concert to compare your recordings with is difficult if not impossible any more.

![]()

Putting things in perspective, the search for pleasing sound and an emotional experience in sound has been going on for thousands of years. High Fidelity is only an attempt to recreate sound. The search goes much further than that. It covers not only all compositions, but also all instruments, whether they are ancient primitive devices or sophisticated electronics--whether it be a primitive didjeridu or keyboard synthesizer.

I have believed ever since the 1950's that ultimately sounds could be created to evoke any reactions that are desired. Sound can be truly three-dimensional when it can be above, below, behind, close or far away--anywhere at all. Sounds can be of great intensity that can physically shake you or so faint they can barely be heard. Depth and spaciousness can lead your imagination and take you on a journey that can build giant, majestic acoustic clouds that drift around you. They can be as quiet as tiny tinkling chimes that travel in a sphere around you, closer and then farther away into remote distances or reverberate endlessly in 3 dimensional space. They can be a musical composition, or an assembly of sonic impressions that create specific reactions--like fine wine. There's no limit. Pure sonic experience leads to the greatest prize of gaining greater self-understanding of our own behavior.

Does this mean that I reject the sound of the live mighty Wurlitzer or the non-enhanced symphony orchestra or my violin? Never!! There's still a favorite place for it and always will be, but it isn't the only sound in town. I continue to pursue the pleasure and the escape of a sonic Nirvana.

Despite what seems to be a departure from the goals of high fidelity, there are some fundamental elements that are retained, whether it is the original acoustic instruments or an electronic composition that can be reproduced by speakers. The overall sound must be smooth in response to be pleasing. A violin and other instruments are made to produce uniform acoustic loudness over the musical scale. Having some notes louder than others is not pleasing. So, in electronic music, the sound of the electronics from the loudspeaker must be smooth, meaning the response does not have peaks and dips. Unless intentionally added by the composer, the reproducing system must also have low distortion, wide bandwidth and wide dynamic range.\\\

![]()

Courtesy of Farside

![]()

Audio Equipment That I Have Owned

|

3-tube AC/DC amplifier |

McIntosh MR65B FM tuner |

![]()

|

About This Site |

||

|

|

More text and pictures about my experiences in sound will be added as my research continues. Any comments, corrections, or additions are welcome. |

|

|

Email

to |

|

All

contents are copyrighted |