War of the Worlds

Compiled by Roger Russell

What is on this page?

It all started with the story written by H.G. Wells many years ago. As many of us know, the story was modified by Orson Wells and broadcast on Halloween night as a radio drama. This story took place in the New York City area instead of London. It caused quite a stir as some people thought it was a real newscast. As far as I know, it was never broadcast in the New York City area again until the early 1960s on WBAI-FM during an afternoon. This page is devoted to the 1953 movie based on the story.

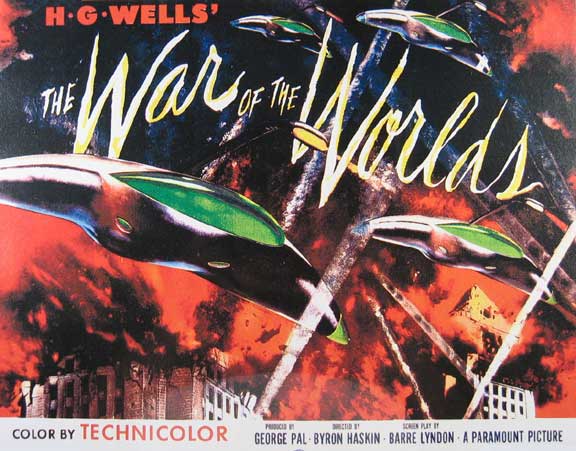

In my opinion, the Martian war machines were perhaps the most imaginative and superb creation ever made for science fiction films. The abstraction of the manta ray shape with its pure simplicity and design for function makes it fascinating and I never tire of looking at it. Although George Pal directed this movie, it was Art Director Albert Nozaki who created the machines. The machines and the sounds were used in one other movie...Robinson Crusoe on Mars. Albert Nozaki also worked on this film. It's likely that simple drawings based on the Martian war machines were used as the alien space ships rather than three-dimensional models.

![]()

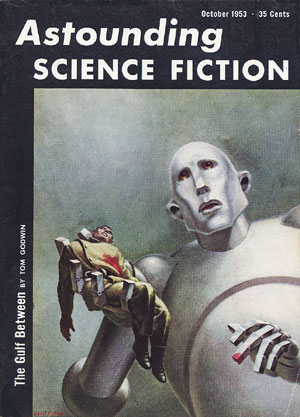

The following article by George Pal was published in the October 1953 issue of Astounding Science Fiction (cover photo shown below), a magazine that I subscribed to in those days. It was unusual at that time for the editor, John W. Campbell, Jr. to have published an article about a science fiction movie but I can only agree that this outstanding movie deserved recognition. The film was released in 1953 and although it has been remade a couple of times recently, they never capture the excellent workmanship that existed back then and the modern design of the Martian war machines has never been surpassed. The movie itself is now 54 years old.

"WAR OF THE WORLDS

You'll see the movie‑it's a good show. But it's

also the end result of

technical feats that any laboratory man can appreciate! The Special‑Effects

man, today, combines inspiration with perspiration ~ using lots of both!

BY GEORGE PAL

Producer of "War of the Worlds," a Paramount Picture

Whenever a Hollywood producer brings out a new motion picture in which he has tampered with the plot of a well‑known novel or play, he's inviting criticism. We took that risk when we made the H. G. Wells classic, "War of The Worlds," but inasmuch as none of us connected with it have been dodging any verbal tomatoes since, I take it that the audiences approve.

"War of the Worlds" was on my agenda of future projects almost since the day I arrived at Paramount Studio two and one half years ago after producing my first science‑fiction venture, "Destination Moon" for Eagle-Lion release. Paramount had owned the Wells story for some twenty‑six years 'but no producer had ever tackled it, although it had been discussed several times. But now with the big vogue for films of a science‑fiction nature it seemed a logical choice. So it was natural that I selected it as one of my first story properties for future production. I was stimulated by the problems it posed. Although written fifty‑six years ago, in many respects it had withstood the advances of time remarkably well and remained today an exciting and visionary story of the future. It offered me my greatest challenge to date in figuring out how to film the Martian machines, their heat and disintegration rays and the destruction and chaos they cause when invade Earth.

It ended up by being my costly picture to date, $2,000,000, as contrasted with $586,000 for Destination Moon," and $936,000 for "When Worlds Collide." It also took the longest period of time to make. More than six months of special‑effects work plus an additional two months for optical effects were needed after our regular shooting schedule with the cast was concluded; work with the cast took forty days at the studio and on location in Arizona.

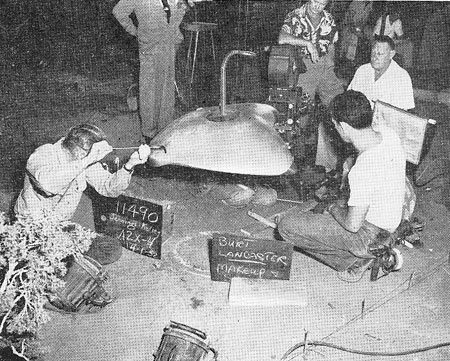

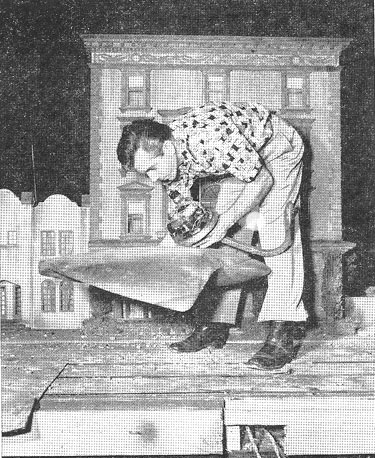

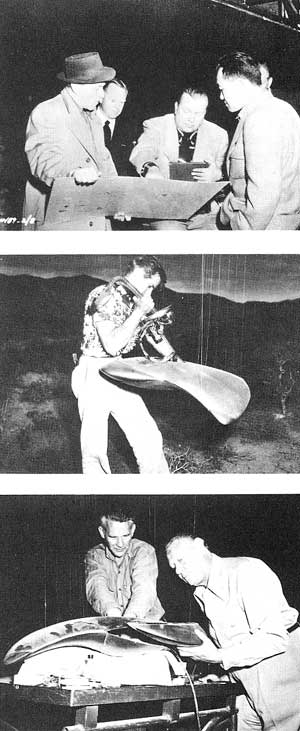

The filming of a science‑fiction movie requires

a series of technical triumphs

in the model shop. Here, the operating mechanism of a heat‑ray that

has

to work practically is installed in a Martian flying wing.

More special‑effects work went into War of The Worlds" than any of my other pictures. More than four times as many, for instance, as went into "When Worlds Collide." Actually one half of the final completed picture which you see on the screen consists of some form of special effects created by our exceptional department here at Paramount Studio.

It is my great sorrow that my good friend Gordon Jennings, Paramount Special‑Effects Director for more than two decades, a multiple Academy Award winner and the recognized leader in his field died of a heart attack shortly after we finished work on the picture and before it was shown publicly. If for one moment you think the challenge of modernizing Wells' story was child's play, just take a scrap of paper and list the commonplace inventions and scientific discoveries which we utilize in our daily living that were utterly nonexistent when Wells wrote his story. There were no airplanes, atom bombs or tanks with which to fight the Martian machines at the time he wrote his tale. His readers followed his story on a flight of imagination. Our audience comes to the theater today conversant with the terms: nuclear physics, atomic fission, gravitational fields and space platforms. Even the children play with space helmets and ray guns and are even more familiar with such expressions as "blast off " than their elders.

It was exciting to take Wells' imaginative work and couple it with modern discoveries and come up with a film that would be entertaining, credible and believable to an audience geared to scientific awareness. One of our first decisions was to move the setting from London and environs to Southern California. It was more practical to shoot in an easily accessible area. Also influencing our decision were the many, stories of flying saucers in the last few years which have emanated from the western part of the United States. Our audiences might well believe that such a Martian invasion could take place in such a locale.

Los Angeles as the metropolis invaded by the Martians was a logical choice, too, because it was possible for us to arrange to actually clear a portion of the city streets of the populace for several of our scenes. I'll wager that if I could climb into the Time Machine which Wells wrote about in another story and flash back fifty‑six years for a conference with the gentleman, he'd have approved the changes. Now how he would have taken our addition of a romantic interest I won't hazard a guess. But in the film business you have to be practical. No one is less interested in doing routine boy meets girl stories than 1. But a boy-and-girl theme is necessary even in a science‑fiction film of the scope of "War of the Worlds." Audiences want it. So we introduced a young college scientist played by a talented newcomer named Gene Barry. As his companion we cast Ann Robinson, another bright new talent.

In one respect we hewed right to the Wells original. That was in his conception of a Martian being. He dreamed up an octopuslike creature. We made ours a huge crablike being with one giant Cyclops eye with three separate lenses, a big head to hold its oversize brain, and long spindly tentacles with suckers on the end for arms. The Martian was the handiwork of our talented young unit art director Albert Nozaki who worked throughout with us from start to finish under Paramount supervising art director Hal Pereira. After Nozaki finished his design I called in a sculptor, make‑up man and artist named Charles Geniora, who became famous as the gorilla in the film " Ingagi " years ago. I asked him to build the monster. He built it out of papier-mache and sheet rubber, created arms that actually pulsated‑through the use of rubber tubing in them‑and painted the whole thing lobster red. It was a startler all right, something right out of your worst nightmare.

Gemora is a short‑statured man who could fit into the contraption too, so we hired him to operate it. When lie got inside he moved around on his knees, holding his arms hunched out. His hands came just to the elbows of the Martian's formidable looking tentacles. Then we showed only one fleeting glimpse of the creature in the final picture! All that effort, money and time for a few seconds on the screen. Why? Naturally there was an argument on how much the Martian was to be shown in the finished picture. But we decided that a hint of horror is often more effective than a large dose. And anyway, would you have wanted to know this thing intimately?

Our greatest special‑effects problem in the production was building and operating the warlike Martian machines which land on Earth to destroy its inhabitants. We came close to electrocuting our crew in designing this one. We went back to the original Wells book for inspiration. My first edition is illustrated with scenes of a huge, disklike object on giant stilts. However, Wells' conception of the machines was mechanical. In this era we decided ours should be electrical. I wish we'd never seen the illustrations of the stiltlike legs at all! We'd have saved a lot of grief. For the original plan, worked out by the special‑effects people, was to have the machines, which were to be miniatures, rest on three pulsating beams of static electricity serving as legs. The idea was to use a high‑voltage ‑electrical discharge of some one million volts fed down to the legs from wires suspended from an overhead rig on the sound stage. A high velocity blower was used from behind to force the sparks down the legs. We made tests under controlled conditions on our special‑effects stage and they were spectacular. I couldn't have been more delighted,

Technicians, rather than actors, dominate the movie

lot; the job calls for

the closest co-operation between photographic technologists

and model show experts. What one can't do, the other must!

But there was one great problem. It was dangerous to generate a million volts on a regular sound stage. It would be too easy for the sparks to jump to damp dust, dirt, metal, or what have you. It could have killed someone, perhaps set the studio on fire. So after the test opening scene we reluctantly gave up the electrical legs for the machine, although a great deal of hard work had already been expended on them. It was in actuality as dangerous as we had wanted it to be on the screen! The Martian machine and its destructive rays, although looming large on the screen, in reality was scaled down to one sixth real size when we filmed it. We built three miniature machines, forty‑two inches in diameter and made out of copper to maintain the reddish hue always identified with Mars, the red planet. They were flat, semi‑disk shaped objects. We gave them three distinctive features, a long cobra neck which emitted a disintegrating ray, an electrical TV camera type scanner on the end of a snakelike metal coil which emerged from the body of the machine, and wing‑tip flame throwers. Each machine was operated by fifteen hair‑fine wires connected to a device on an overhead track. By means of these wires we carried the electrical controls to make the cobra neck, the scanning eye and other portions operate properly.

This was indeed puppetry on a huge scale! Here is another trade trick on how we made the triple‑lensed scanner: It was actually thick plastic with hexagonal holes cut in it. Behind these, rotating light shutters gave a flickering effect. But in creating the flicker we got into fresh trouble. We got a strobatach effect, the sort of thing you see in a movie of wagon wheels in which the turning spokes seem to go faster, then slower when they are in conflict with the camera shutter speed. Our answer was to very carefully regulate the shutter speed behind the head. Those vicious‑looking fire rays emanating from the machines were burning welding wire. As the wire melted, a blow torch set up behind, blew the wire out. The finished result looked highly realistic.

Before we ever started shooting the picture, more than one thousand sketches were prepared by Nozaki supervised by Art Director Pereira, working in close collaboration with Director Byron Haskin. These showed their conception of how combined live action and special effects, or each of them separately, would look. Originally, they were rough sketches but by the time we were ready to begin shooting in January, 1952, detailed drawings were completed and inserted at the proper places in the script to guide Director Haskin, Cameraman George Barnes, A.S.C., and the rest of the crew. It isn't customary to detail so carefully what each scene and camera setup will look like but in a science fiction film of this type, it is vitally necessary to hold down costs and production time.

Nozaki's drawings were especially valuable in the extensive sequence showing the evacuation of Los Angeles and the attack on the city by the Martian machines. Both live action and special‑ and optical‑effects were extensively mixed in these complex scenes. In addition to shooting the downtown section of Los Angeles in real life, we created it in miniature on a Paramount sound stage. Miniatures are becoming a worse headache with each picture made. I've learned that even the bobbysoxers can spot them in most films these days. We absolutely had to maintain an aura of credibility and authenticity for our story. This tends to give those expensive ulcers to special‑effects men and producers you read about. As a result we built miniatures more carefully than ever before. We strove for lifelike authenticity by making them larger. Our Los Angeles City Hall miniature, for example, was eight feet tall. Quite a few experts told me that they couldn't distinguish between the miniatures and the real thing which really made me feel proud.

A check was made with Civil Defense Authorities before staging the evacuation scenes in order to incorporate the latest techniques for such an emergency. Automobiles, rather than tuxedos, were the requirements for the nine hundred extras hired for the sequence. We wanted a traffic jam. One of the scenes turned out to be unrehearsed real life. During the filming we heard one day that there had been a crash on the new Hollywood Freeway which had caused a bad traffic tie‑up. A camera crew was rushed to the spot like a newsreel staff and caught the scene. We needed a deserted city. Ours was Los Angeles at 5:00 a.m. on a Sunday morning. Its normally clear streets at that hour were enforced by police outposts hooked up with our company by walkie‑talkie. It was hard work to frame a panic evacuation scene‑but even more work to clean up the fallen masonry, rubble, papers, and trash scattered for blocks up and down the center of one of America's largest cities afterwards.

Here's an example of how we tied in special‑effects with the real‑life evacuation: We photographed a street on a back lot. With this we matched four by five Ectachrome still shots of Bunker Hill in downtown Los Angeles. These were rephotographed on Technicolor film. A hand‑painted matte, done on an eight by ten inch blowup, then reduced to regulation 35 mm. film frame size, of the sky, background, flame effects and the Martian machines was then matched with the live action. This complicated business is accomplished in the special‑effects camera department with large, expensive, custom‑built, optical printers under the direction of Paul Lerpae, a veteran in the business. He has optical printer cameras mounted on lathes with adjustments calibrated down to 1/10,000 of an inch. It has It has to be in that great detail. The tiniest mistake made on a single film frame is magnified two hundred times on a average‑sized screen, even more on the new wide screens now coming into vogue.

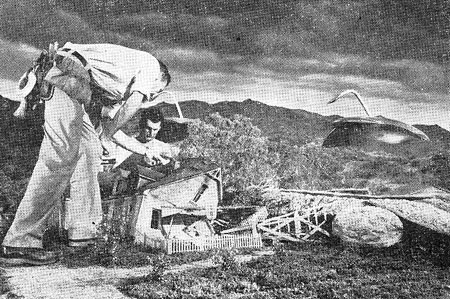

Realism is earned; it doesn't just happen. For the

horse‑opera, any piece of Western

desert scenery will do; "realism for free" is available to

them.

For science‑fiction films, it's the reward of infinite pains with

details.

For "War of the Worlds," the optical‑effects department painted between three thousand to four thousand celluloid frames for us. In one brief flash in the picture an army colonel is disintegrated by a Martian machine. It took exactly one hundred forty‑four mattes of his inked‑in figure to accomplish this illusion. But everything I've described so far was just a practice session for the biggest hurdle of them all. The single, most difficult sequence to create in the entire picture‑was when the United States Army attacked the Martian machines and they fought back.

"No, children, they didn't really destroy Los

Angeles to make this movie.

But my, wouldn't you like to have what they did have to destroy‑after

months of the most painstakingly exacting efforts!"

First we did the easy part‑the live action with our cast and the National Guard on location near Phoenix, Arizona. For two days the outfit went through maneuvers while our cameramen shot scenes of them defending our country against Martians. Then the special‑effects boys went to work. First, matte shots of trees and a command post were made. Then miniatures of a gully where the actors could hide, and the approaching three Martian machines were photographed. Next the rays and explosions were inserted. After that came the bright yellowish foreground explosions. In all we had five complicated processes to contend with. At times we made as many as twenty‑eight different exposures to get one single final color scene. For a scene where an attacking tank is disintegrated, we inked in the tank outline on an opaque matte. Then we changed the color to red, then to redblue. We got a flaring out of sudden flame from the tank by using diffusion glasses. Here was the spot where we switched from red to yellow. Afterwards we photographically "dodged in" the burnt areas around the area where the tank had been.

When the United States forces drop an atom bomb on the Martians we had to come up with a gimmick to protect the invaders in this crisis. Special‑effects devised a large, plastic bubble, five feet in diameter. First, the machine was filmed alone. Then we photographed the explosion and the bubble and superimposed that negative over the first to get the final result. There was no clearance needed for the facsimile of the atom bomb we used. It was a stunt engineered right on our own sound stage by Paramount's eighty‑one‑year‑old powder expert, Walter Hoffman. He got his effect by putting a collection of colored explosive powders on top of an air‑tight metal drum filled with an explosive gas. Rigged up with an electrical remote control, its second try reached a height of seventy five feet with the mushroom top of the real thing.

To build a perfect miniature house is a job; how they

achieved the common,

familiar pattern of weatherstoining, though, is probably a trade secret.

And it's unquestionably a high art!

Getting Army clearance was not a major concern in producing "War of the Worlds." We did use a few stock shots from the Northrop and North American Aviation Companies which bad to be submitted to the Department of Defense, but it was minor. One of these was a shot of the Flying Wing which we used to carry the atom bomb against the Martians. While producing both "Destination Moon" and "When Worlds Collide," I bad employed the unique talents of artist Chesley Bonestell. I naturally wanted him back for "War of the Worlds." When he came, he served a double role. A series of his paintings of the planets in our solar system were shown during the prologue with the voice of Sir Cedric Hardwick impersonating that of H. G. Wells in describing why the Martians were forced to migrate from their planet. He explains why Earth was the only one that would do.

Most of Bonestell's paintings were made on canvas of standard size but in the case of Jupiter he painted on glass. He created a mural seven by four feet showing Jupiter's rugged terrain leaving cut‑out areas in order that the special‑effects department could insert lifelike looking streams of molten lava coursing down the mountainsides. How would a Martian scream sound? The boys thought a long time on that one. Finally they arrived at the unusual conclusion of scraping dry ice across a contact microphone and combining it with a woman's high scream recorded backwards. It was the weirdest sound anyone has yet come up with for one of my pictures. The vibrating, almost singing noise of the machines themselves was a magnetic recorder hooked up to send back an oscillation sound. The eerie sound of the Martian's death ray was chords struck on three guitars, the sounds amplified, then played backwards and reverberated.

Although it took months to come up with the sounds, once we had them it was a simple matter to record them in the picture.

The nerve strain or co‑ordination in a film like "War of the Worlds" is tremendous. Let one department fluff off and the whole result goes flooey no matter how the others have knocked themselves out for perfection. You get so wrapped up in your own particular problems and your part of the teamwork that by the time the film is in the can, the whole thing is sort of a haze. You've knocked yourself out on details and technicalities so that when someone asks you, "Is it good," you can't answer "yes" or "no" for sure. The whole thing is a blur. A conventional picture is easier to produce and judge.

That's why the first sneak preview at the Paradise Theater in Westchester, a Los Angeles suburb, last November had all those who worked on the film slightly off this world's gravity. We'd used our imagination and ingenuity‑given it everything we had. Was it good or was it ripe for blase teenagers' laughter? It was a fine feeling which the cast and creators shared when the preview cards came in "good." just to make sure that this favorable audience wasn't an exception, we staged a second sneak preview in Santa Monica. Another top response. Then we really relaxed. Those Friday night audiences of youths from twelve to twenty‑five in jeans and leather jackets are the toughest audiences in the world to please. We were satisfied that, if they took our version of H. G. Wells, we'd made the grade. Uncurling our fingers, almost arthritic with crossings, the print was shipped to New York. But was it time to vacation? Not by a planetful. Now let's see: If we got disintegration in" War of the Worlds, " can we create artificial satellites in " Conquest of Space "? I hope so. It's the next science‑fiction film on the agenda, you know.

THE END

![]()

Promotional picture of Gene Barry and Ann Robinson

![]()

Text and pictures in the following article are courtesy of the book titled Twenty All-Time Great Science Fiction Films by Kenneth Von Gunden and Stuart H. Stock and published in 1982.

PRODUCTION CREDITS

|

PRODUCER . .George Pal DIRECTOR .. ..Byron Haskin SCREENPLAY . . Barre Lyndon ASSOCIATE PRODUCER . .. Frank Freeman, Jr. DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY ..... .Georje Barnes, A.S.C. ART DIRECTION ... ...Hal Pereira and Albert Nozaki EDITOR . . Everett Douglas, A.C.E TECHNICOLOR CONSULTANT . .. ..Monroe W. BurbankI ASSISTANT DIRECTOR . ..Michael D. Moore COSTUMES Edith Head SET DECORATION . .. .Sam Comer and Emile Kuri MAKEUP SUPERVISION .. ... Wally Westmore MUSIC .. .. .Leith Stevens SOUND RECORDING .. Harry Lindgren and Gene Garvin SPECIAL PHOTOGRAPHIC EFFECTS . . .Gordon Jennings-, A.S.C., Paul Lerpae, A.S.C.Wallace Kelly, A.S. C. Ivyl Burks, Jan Domela and Irmin Roberts, A. S. C ASTRONOMICAL ART ... . .Chesley Bonestell MARTIAN COSTUME AND MAKEUP .. Charles Gemara HAIR STYLIST . ... .Nellie Manley PROCESS PHOTOGRAPHY Farcoit Edouart, A.S.C. MINIATURE CONSTRUCTION ..Marcel Delgado SPECIAL EFFECTS .. Walter Hoffman PROPERTIES .. Gordon Cole STUNT COORDINATORS .Dole Van Sickel, David Sharpe and Fred Graham

CAST |

|

CLAYTON FORRESTER.... .. ... Gene Barry SYLVIA VAN BUREN . . Ann Robinson GENERAL MANN ....Les Tremayne DR. PRIOR ...... .. ..Robert Cornthwaite DR. BILDERBECK .... ..Sandro Giglio PASTOR MATTHEW COLLINS ...Lewis Martin GENERALs AIDE ... ..Housely Stevenson, Jr. RADIO ANNOUNCER ..Paul Frees WASH PERRY ...Bill Phipps COLONEL HEFFNER .Vernon Rich COP .Henry Brandon SALVATORE ... ..Jack Khruschen PROFESSOR MCPHERSON Edgar Barrier BUCK MONAHAN Ralph Dumke DUMB BLONDE ..Carolyn Jones MAN Pierre Cressoy MARTIAN .Charles Gemora SHERIFF BOGANY ...Walter Sande DR. JAMES ...Alex Frazer DR. DUPREY .Ann Codee DR. GRATZMAN ..Ivan Lebedoff RANGER ...Robert Rockwell ZIPPY Alvy Moore ALONZO HOGUE ..Paul Birch FIDDLER HAWKINS ..Frank Krieg WELL‑DRESSED LOOTER ..Ned Glass LOOTERS ... ...Dave Sharpe, Dale Van Sickel,and Fred Graham PROLOGUE NARRATOR . Paul Frees |

The War of the Worlds (hereafter referred to as War), which had been a Paramount property since 1925, became one of the first alien invasion films of the fifties. Filmed in magnificent three- strip technicolor, the $2,000,000 film proved that "a special effect is as big a star as any in the world," as George Pal later said of the success of Star Wars.

While Pal's film version lacks the depth and resonance of H. G. Wells's novel, it is a stunning success in purely visual terms, with its menacing Martian machines gliding relentlessly across the screen, scattering mankind before them and leaving total destruction and death in their wake.

When Paramount licensed War for video cassette sales in 1980, it quickly climbed into the ranks of the top twenty‑selling tapes, its appeal undiminished nearly thirty years after its release.

War was generally well received by the critics when it premiered in New York on August 13, 1953 (it had a Hollywood‑only premiere on February 20, 1953). The New York Times said: "The War of the Worlds is, for all of its improbabilities, an imaginatively conceived, professionally turned adventure which makes excellent use of technicolor, special effects by a crew of experts, and impressively drawn backgrounds.... Gene Barry, as the scientist, and the cast behave naturally, considering the circumstances."

Moira Walsh, writing in America, called the film a surprisingly pertinent and undated science fiction account of an invasion from Mars.... Its technicolored 'special effects' (bv the late Gordon Jennings) are superlative and its scientific explanations are lucid and convincing. By comparison, its handling of earthly matters, such as mass panic, boy meets-girl (yes, even here!) and a well‑intentioned but rather sappy affirmation of religious faith, is rather flat and small in conception."

The titles appear after a brief prologue (read by Paul Frees) detailing the ever greater destructive power of modem weapons. A narration, read by Sir Cedric Hardwicke, describes the Martians' need for a new world and precipitates a two-and-a-half minute "grand tour" of the solar system, ending with our green and inviting Earth.

The residents of Linda Rosa, a small California town, see a meteor fall to Earth, skidding in sideways and starting a number of small brush fires. Word of the fallen meteor is sent to three Pacific Tech scientists fishing in the area. Dr. Clayton Forrester, one of the scientists, decides to take a look.

Meanwhile, at the impact site, a gully, the townspeople gather to stare at the still‑hot meteor and discuss the economic benefits it could bring Linda Rosa through increased tourism.

Forrester, a nuclear physicist, arrives at the site, where he meets Sylvia Van Buren, niece of Pastor Matthew Collins, the local minister, and a lecturer in Library Science at USC. When Forrester's Geiger counter starts clicking, indicating the meteor is radioactive, he decides to stay until the meteor cools.

While Forrester, Sylvia, and the rest of the town attend a square dance that night, three locals are deputized to stand guard near the meteor while it cools. They're about to leave when they hear a strange sound‑the top of the meteor is unscrewing! A long-necked, cobra‑headed probe emerges from the opening. Eager to make "first contact," the locals, waving a white flag ("Everybody understands when you have the white flag, you wanna be friends," says one), slowly approach the ominous‑looking cobra head. Their words of welcome turn to screams as the cobra he‑ad turns and drops toward them, a strange pinging sound preceding the release of a heat ray that incinerates them.

At the dance, the lights and phones go out, and all the clocks and wristwatches become magnetized; a compass points toward the meteor site. Forrester, the sheriff, and a deputy rush there to discover fires, downed power lines, and the charred bodies of the three men. As they survey the scene in horror, they spot the cobra neck turning toward them, the waning pinging increasing in intensity. The deputy tries to flee in the police car, leaving Forrester and the sheriff behind, but he's destroyed by a blast from the Martian heat ray. Forrester and the sheriff escape on foot and call in the military.

Quickly mobilized, the Army rushes vehicles full of troops to the gully harboring the Martian machine. As the troops continue digging in, an Air Force plane drops flares. The flares reveal a manta rav‑shaped Martian machine, now free of its protective meteor casing. The machine fires its heat ray, destroying a radio truck, and everyone dives for cover. Still more troops and tanks are called up to encircle the Martian nest with a ring of steel. Colonel Heffner arrives to take charge of the operation. Sylvia, there with her uncle Matthew, serves donuts and coffee to the weary soldiers. Soon Colonel Heffner is joined by General Mann, who notes the Martians' position and reveals the machines are magnetically linked in groups of three.

Forrester (Gene Barry) and others from the church venture out to find all the Martian

machines have crashed. Here. A dying Martian feebly reaches out from a hatch in its machine

After a long and tension‑filled night, the troops wait for something to happen. A Martian machine rises from the gully and surveys the scene. In the command bunker, Pastor Collins argues for peaceful communication with the Martians, theorizing they must be closer to the Creator than man, since they are technologically more advanced. Slipping undetected from the bunker, he walks toward the trio of approaching machines, a Bible in his hand, reciting the twenty‑third Psalm. The cobra neck of the lead machine swivels and drops menacingly toward him, then blasts him with its heat ray.

Shocked at the minister's incineration, the troops open fire. The gully around the machines is devastated by the firepower of the soldiers, but the machines themselves are unharmed, protected by translucent blisters. Using their heat rays and "skeleton" rays (so called for their effect), the machines vaporize the soldiers and their ineffectual weapons. The headquarters bunker is hit by a heat ray, turning one soldier into a human torch. Colonel Heffner orders everybody out, but is himself caught in a skeleton ray and disintegrated.

Forrester and Sylvia escape in his small airplane while jets streak toward the Martian machines. Flying low to avoid the jets, Forrester nearly collides with a Martian machine and crashes near an abandoned farmhouse. Later, rested and recovered from the crash, Forrester and Sylvia cook breakfast in the farmhouse. Sylvia tells him of a time when she, a child and lost, took refuge in a church and "prayed for the one who loved me most to find me." She was found by her uncle Matthew.

A new meteor smashes into the farmhouse, collapsing it and knocking Forrester unconscious for several hours. After he awakens, a Martian machine hovers outside, looking for life.

As Forrester and Sylvia prowl around, one of the machines lowers an electronic TV-eye on a flexible cable. Entering through a window like some great snake, the eye investigates the room the two frightened humans are hiding in. Finding nothing, the eye closes up protectively and withdraws, but another one appears after Sylvia catches a fleeting glimpse of a Martian outside. Alerted to the presence of the Martian scanner by Sylvia's scream, Forrester severs the eye from its cable with an axe.

Suddenly, a Martian lays his suckered hand on Sylvia's shoulder. Forrester throws a length of pipe at the creature‑after first shining his flashlight on itand it runs off shrieking in pain.

Calming the hysterical Sylvia, Forrester realizes there is no time for romance. Taking the severed probe with them and a sample of the Martian's blood, they escape from the farmhouse moments before the Martians destroy it.

The rout of mankind is shown through scenes detailing the Martians' destruction of Earth's greatest cities. Man seems helpless before the superior weaponry of the Martians.

At his command post, General Mann reveals the Martian battle strategy of linking up in threes and cutting through the countryside like scythes. Meanwhile, Forrester arrives at Pacific Tech with the electronic eye he severed and the blood sample from the wounded Martian. The Martian eye has three segments, each with its own pupil and each a different color: red, blue, and green. Hooking up the scanner to an "epidiascope" reveals how the Martians see us.

Since ordinary weapons are useless, an atomic bomb, carried by the "flying wing," will be dropped on the Martian position outside Los Angeles. A radio man records the scene on tape outside the bunker nearest the Martian advance, his words meant for the future-if there is any.

The Martians generate their protective blisters as the bomb is dropped. The onlookers, including Forrester and Sylvia, peer through goggles at the radioactive cloud, searching for signs of life. Suddenly, the Martian machines glide unscathed ‑from the cloud. Man has thrown the best of his military arsenal at them to no effect. Their inexorable advance continues. Los Angeles is next.

At Pacific Tech, Forrester advocates a biological approach to defeating the Martians, since "we can't beat their machines." But the Martians are approaching the city, and an evacuation is ordered. Unable to continue their research in the city, the Pacific Tech scientists flee in a school bus driven by Sylvia. Forrester stays behind to retrieve some instruments, planning to drive out in a pickup truck. But he encounters looters desperate to escape, who beat him and throw him from the truck. Left behind, his truck gone, Forrester runs through the empty streets. He finds the truck, overturned and stripped, but the only sign of Sylvia's school bus is its destination sign lying in the street.

The Martian machines glide malevolently down the nearly empty streets of Los Angeles, their heat rays blowing up buildings, water towers, and even the Los Angeles City Hall. Explosions and flames all around him, Forrester runs from church to church looking for Sylvia. Forrester finds several Pacific Tech scientists who left on her bus, but she is not with them.

Finally, in the third church he visits, Forrester finds her. The situation seems hopeless, and they embrace amid the impending destruction of the church. Suddenly, the Martian machines slow and crash to the street. As Forrester and Sylvia go outside to investigate, they see a hatch on one of the machines open. A suckered hand emerges and flexes feebly before it stops moving. The Martians are dead, killed by our bacteria.

Sir Cedric Hardwicke's narration thanks God, saying, "And thus, after science fails man in its supreme test, it is the littlest things that God in his wisdom had put upon the Earth that save mankind."

In 1895, the twenty‑nine‑year‑old H. G. Wells moved to a house in Woking. There, working diligently on the dining room table, Wells wrote many of his best‑known short stories and three novels: The Wheels of Chance (a cycling romance), The Invisible Man, and The War of the Worlds. Wells, like many Englishmen of his day, had succumbed to the joys of the safety bicycle, and he began to keep accounts of his cycling adventures and the sights he saw while pedaling around Woking.

Wells's brother Frank suggested he write a work detailing an interplanetary invasion. Intrigued by the suggestion, Wells began to work out the plot. In his autobiography Wells wrote how he "wheeled about the district marking down suitable places and people for destruction." And, in a letter to Elizabeth Healey, he wrote: "I'm doing the dearest little serial for Pearson's new magazine, in which I completely wreck and sack Woking‑killing my neighbors in painful and eccentric ways‑‑then proceed via Kingston and Richmond to London, which I sack, electing South Kensington for feats of peculiar atrocity."

The novel was well received when it appeared in 1898. Sir Richard Gregory's review in the February 10th issue of Nature was typical of the novel's critical success: ". . . The War of the Worlds is even better than either of these contributions [The Time Machine and The Island of Doctor Moreau] to scientific romance, and there are parts of it which are more stimulating to thought than anything that the author has yet written."

The feeling of impending apocalypse that colors all of Wells's early works, the "scientific romances," is present in War and is the result of several factors in Wells's background. For one, Wells, who was often in poor health, feared he would die young. Further, his early religious training continued to affect his outlook, suggesting to him that Man, the imperfect animal, might fall from his lofty place in the scheme of things. Finally, Wells was influenced by scientific theorists who argued that the law of entropy would lead to a cooling of the sun and the ending of all life on Earth and the other planets of the solar system.

War fits comfortably into the "end of the world" tradition that has been the source of so much religious imagery. Wells was to use several variations on the end of the world theme in his works: In the Days of the Comet (a collision between a heavenly body and the Earth), The World Set Free (a massive explosion), and The Shape of Things to Come (the descent to Earth of Angels to establish the Kingdom of God).

Wells's War also followed the appearance, during the final third of the nineteenth century, of a multitude of novels and works detailing the successful invasion of England, including the first, Sir George Chesney's The Battle of Dorking (1871), Sir William Butler's The Invasion of England (1882), William Le Quex's The Great War in England in 18.97 (1894), and F. N. Maude's The New Battle of Dorking (1900).

These works were the expression of a prevalent mood known as Fin de siecle, or "end of the century, age, world." Fin de siecle results most often when art and behavior undergo transformations, and the old and familiar forms disappear or are replaced by new forms which seem strange or even bizarre, The nineteenth century had been full of momentous change and overpowering events. There was a longing for a new beginning, a new century in which to rebuild the social and intellectual order that fast‑moving events had pushed to the brink of collapse.

Later historians were amazed when, Sir George Chesney's book in hand, they were able to find all the geographical landmarks in and around Dorking he mentioned in his fictionalized account. Here again, Wells followed Chesney's example. He, too, made references to actual places devastated by the Martian invasion‑the result of his cycling excursions. Real names like Winchester, Berkshire, Surrey, and Middlesex add to the almost documentary-like flavor of War.

Wells's War was perhaps the first book to show mankind on the run, fleeing before a merciless enemy. While such scenes are all too familiar to twentieth century man, used to newsreels showing refugees from countless wars, they were startlingly fresh and powerful in 1898:

For the main road was a boiling stream of people, a torrent of human beings rushing forward, one pressing on another. A great bank of dust, white and luminous in the blaze of the sun, made everything within 20 feet of the ground grey and indistinct and was perpetually renewed by the hurrying feet of a dense crowd of horses and men and women on foot, and by the wheels of vehicles of every description.

So much as they could see of the road Londonward between the houses to the right was a tumultuous stream of dirty, hurrying people ... the black heads, the crowded forms, grew into distinctness as they rushed toward the comer, hurried past, and merged their individuality again in a receding multitude that was swallowed up at last in a cloud of dust.

Wells was responsible for other firsts in War, most notably the first real alien in literature, as opposed to a giant man in Voltaire's Micromegas. Here is Wells's description of Man's first encounter with a truly extraterrestrial life form:

A big greyish rounded bulk, the size, perhaps, of a bear, was rising slowly and painfully out of the cylinder. As it bulged up and caught the light, it glistened like wet leather.

... There was a mouth under the eyes, the lipless brim of which quivered and panted, and dropped saliva. The whole creature heaved and pulsated convulsively.

... The peculiar V‑shaped mouth with its pointed upper lip, the absence of brow ridges, the absence of a chin beneath the wedge‑like lower lip, the incessant quivering of this mouth, the Gorgon groups of tentacles.... There was something fungoid in the oily brown skin, something in the clumsy deliberation of the tedious movements unspeakably nasty .... I was overcome with disgust and dread.

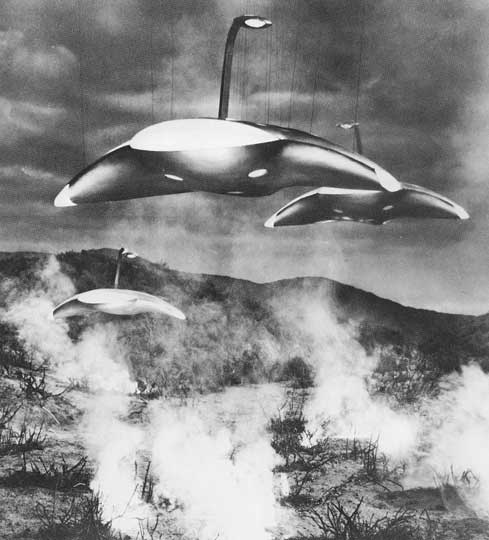

A trio of Martian war machines advance slowly as they move out of the gully

into the face of the intense firepower directed at them. The wires supporting

the lead machines are clearly visible in this shot.

Wells's vile Martians drink human blood, or, rather, inject it into their veins. While this practice disgusts Wells's narrator, he is quick to point out that I think that we should remember how repulsive our carnivorous habits would seem to an intelligent rabbit."

This is perhaps Wells's greatest contribution in War: the turning of the tables, the looking at things from fresh perspectives, especially our treatment of "lower" life forms, including the colored races enslaved or destroyed by the white man's superior technology. As Wells's narrator says, after hiding from the Martians as a frightened rat might hide from men, "Surely if we have learned nothing else, this war has taught us pity‑pity for those witless souls that suffer our domination."

George Pal was born in Cegled, Hungary, a small town about thirty‑five miles from Budapest, on February 1, 1908, the son of entertainers with a traveling theater troupe. Raised by his grandparents, Pal did not follow in his parents' theatrical footsteps, deciding instead to become an architect. In 1925 he was accepted into the Budapest Academy of Art, where, in addition to his architectural studies, he took painting, anatomy, and other fine arts classes. He also slipped into a nearby medical school's lectures on anatomy occasionally by donning a white smock and pretending to be a student. Pal made extra money by sketching muscles and bones for the medical students, which they turned in as their own work.

Architectural students were required to learn either carpentry or bricklaying, so Pal decided to become a carpenter, a craft which would help him immensely when he created his puppetoons.

Architect Pal graduated in 1928, just in time to Join the swelling ranks of the unemployed in Hungary. But his knowledge of anatomy and his drawing skills got him a job as an apprentice animator at Budapest's Hunnia Film Studio. The job enabled Pal to marry his childhood sweetheart, Zsoka Grandjean.

Pal found that his salary, while enough for him, was insufficient for a newly married man, so he looked around for another, better‑paying job. In 1931 he and his wife went to Berlin, where he found work as an animator at the huge UFA studio. Within two months he was put in charge of the studio's cartoon department.

By 1933 Pal found himself under scrutiny by the Gestapo, so he moved to Prague, Czechoslovakia, and set up his own cartoon studio, designing his own portable stop‑motion camera when he discovered there wasn't a single animation camera in the country.

Hoping to find success making animated commercials, Pal moved again, this time to Paris, where he made cartoons for Philips Radio of Holland. Philips Radio liked his work so much they convinced Pal to pack his suitcases again and move to Holland, where he opened his first studio in a garage and his second in a butcher shop. Here, Pal and his American associate, Dave Bader, hit upon calling his "color cartoons in three‑dimensions" puppetoons, a word created by combining puppet and cartoons.

By 1939 war was imminent, and, after several tries, Pal was finally granted a visa to emigrate to the United States, his fifth country in eight years. When Pal reached New York, Barney Balaban of Paramount Pictures saw one of the young Hungarian's puppetoons: at a party and offered him a contract to produce a series of animated shorts to be released under the name "Madcap Models."

Forrester (Gene Barry), flanked by Dr. Pryor on the left (Robert Cornthwaite) and Sylvia

(Ann Robinson) on the right shows the scientists at Pacific Tech the head of the electronic

TV probe that he severed in the farmhouse.

George Pal, left, with Sir Cedric Hardwicke, who narrated the film, at a recording session.

Pal thought it appropriate that an English voice speak Wells's words.

Within a year George Pal Productions of Hollywood, California, was producing puppetoons for Paramount. Between 1941 and 1947 Pal made over forty puppetoons for the studio, receiving six Academy Award nominations along the way. The Academy voted him a special Oscar for his unique animation techniques in 1943.

After producing two educational shorts in 1948 and 1949 for Shell Oil, Pal got the financial backing he'd been seeking from Eagle‑Lion Films to produce his first feature, The Great Rupert, starring Jimmy Durante, in 1949. Rupert was a trained squirrel (really just another animated figurine) who finds a cache of money in an old house filled with destitute vaudevillians and gives it to his friend Mr. Amendola (Durante). The film got good reviews as a family picture and made money. Pal and his director on Rupert, Irving Pichel, were now ready for their next joint effort-Destination Moon. (See the DM chapter.)

Top

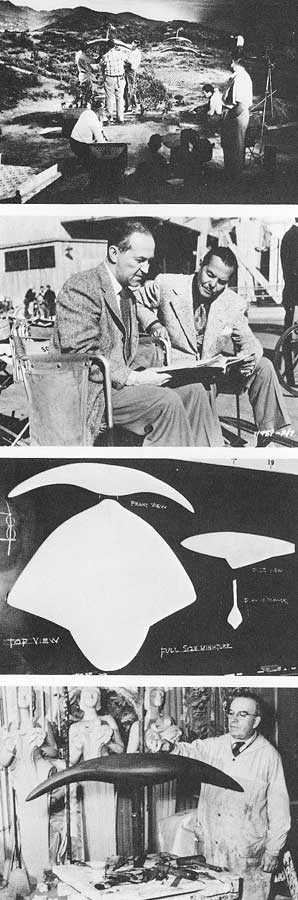

to bottom

Top

to bottom

1. Gordon Jennings, standing, watches the effects crew prepare a Martian machine for filming.

2. Producer George Pal and director of photography George Barnes look over the script.

3. Preliminary sketches of the full‑size Martian machine model on a studio blackboard.

4. A plaster shop employee at Paramount works on the mold which will be used in the making of Martian machines.

Pal's project after Destination Moon was When Worlds Collide. With its successful launching, Pal began looking for another script and was excited to discover that Paramount owned the rights to H. G. Wells's classic The War of the Worlds.

Cecil B. DeMille bought the film rights to War in 1925. In 1926 the New York Times reported Paramount's decision to make the film. "Arzen Doscerepy, famous German technical expert who has been producing in Berlin," said the Times, "has spent two years perfecting devices and mechanisms which will make Wells's Martians walk and spray death around the world."

Hollywood pioneer Jesse Lasky, who'd gained control of Paramount, offered the Wells property to famed Russian director Sergei Eisenstein (Tbe Battleship Potemkin) in 1930. But, although a script was prepared, Eisenstein backed out in favor of Que Viva Mexico (1931), a film never completed. Later War was almost made a number of times, but never got past the writing of the script.

Pal, assured that Paramount owned the rights to the novel in perpetuity, called his good friend DeMille. DeMille quickly told him he was no longer interested in making the film himself and would be delighted to help Pal in any way he could.

Pal started moving ahead on the project and hired Barre Lyndon to write a new script. Lyndon, born in London in 1896, was a former journalist, novelist, and playwright who'd moved to New York from England in 1938. By 1940 he was writing movies for MGM, and in 1943 wrote The Lodger for 20th Century-Fox.

Pal and his director, Byron Haskin, asked Lyndon to update the story and set it in the United States. With all the talk of flying saucers, War was especially timely, and a California-based film would be much cheaper to shoot than a London period film.

After finding the perfect small town in the Chino hills, Linda Rosa, Lyndon began working on his first draft. At Pal's urging, Lyndon replaced his original lead, Major Bradley, with Dr. Clayton Forrester, a nuclear physicist from Pacific Tech.

Pal wanted Forrester to become separated from his wife and child and spend his time searching for them. But Don Hartman, vice‑president in charge of production and the man responsible for the Crosby/Hope "Road" pictures, said a married hero wouldn't be acceptable to the audience. Instead, he ordered Pal to give Forrester a "love interest." Reluctantly, Pat. had Lyndon write in the character of Sylvia Van Buren, as well as reducing the violence in Lyndon's first draft.

When Hartman saw Lyndon's script dated June 7, 1951, he told Pal it was a "piece of crap" and threw it into a wastebasket. But associate producer Frank Freeman, Jr. defended the film to his father and president of Paramount, Y. Frank Freeman, as did Cecil R. DeMille, without whose support the film might never have been made. The elder Freeman told Pal to make the film any way he wanted, and work went ahead.

Pal began casting the picture during the summer of 1951, looking for the right actor for the Clayton Forrester role. He considered Lee Marvin, but instead went with an unknown, a young Broadway actor Paramount had just put under contract, Gene Barry. While waiting for shooting on War to begin, Barry made The Atomic City (1952).

Twenty-four-year-old Ann Robinson, a native Californian who'd had a bit part in George Stevens's A Place in the Sun (1951), was signed to play Sylvia Van Buren.

In December 1951 a second‑unit film crew left for ten days of location shooting near Florence, Arizona, about forty‑five miles southwest of Phoenix. Byron Haskin and another crew were sent thirty‑five miles northwest of Los Angeles to film the evacuation of the threatened city. In the hilly terrain surrounding the Simi Valley, Haskin shot the scenes of onlookers watching the atomic bomb explosion that fails to stop the Martian machines.

The Arizona National Guard played the part of the Army troops, and the scenes of them in their tanks, armored vehicles, and personnel carriers roaring up, jumping out, and setting up in battle positions were totally realistic in comparison with many stock footage-filled films.

Top to bottom

1. George Pal, promotion manager Kenneth DeLand, and

director Al Nozaki study a production sketch.

1. George Pal, promotion manager Kenneth DeLand, and

director Al Nozaki study a production sketch.

2. Lee Vasque, now head of Paramount's prop shop, works on the mechanism which operated the cobra neck and head.

3. Effects man Chester Pate (left) and special effects chief Gordon Jennings, work on a Martian machine.

The gully where the first meteor lands took shape on Stage 18. Albert Nozaki recalled that his stage setting on 18 was basic and designed to be as economical as possible; the production's budget couldn't afford many sound stages.

Meanwhile, Haskin's crew filmed portions of the evacuation from Los Angeles on an unopened segment of the Hollywood Freeway. For the scenes of Forrester searching frantically for Sylvia, Pal got the Los Angeles Police Department to rope off part of Hill Street early one Sunday morning. The police kept the streets clear for the Film company while cameras covered Gene Barry's movements through streets dressed by the prop department.

Shooting the principal photography took about a month, and was finished in mid‑February 1952. Haskin had only been shooting for several days when a lawyer from the legal department ran onto the stage shouting that filming had to stop. The lawyer explained that Paramount owned only the silent rights to Wells's book. But Wells's son Frank was completely sympathetic and got the movie company out of hot water by selling them the "talkie" rights for an additional $7,000.

Stage 18 was cleared for four miniature sets with sky backings, the most elaborate of which was the Los Angeles street destroyed by the marauding Martian machines. A backlot street was matched with 4 by 5‑inch Ektachrome still shots of Bunker Hill in Los Angeles, and rephotographed on technicolor film. A matte of the sky and background, done as an 8‑ by I 0‑inch blowup and then reduced to 3 5 mm film frame size, was matched with the flame effects, Martian machines, and then with the live action.

The miniature street was built on a platform so the high‑speed cameras could not only shoot from street level but also get as close to the miniature buildings as necessary. Filming at approximately four times normal speed requires intense light levels, so the set was bathed in light.

For the effects of the A‑bomb blast, eighty‑one‑year‑old powder expert Walter Hoffman placed a mixture of colored explosive powders atop an airtight metal drum filled with explosive gas on Stage 7. Set off by an electrical charge, the resulting explosion reached a height of seventy‑five feet and produced a perfect mushroom cloud for the high‑speed cameras filming the miniholocaust.

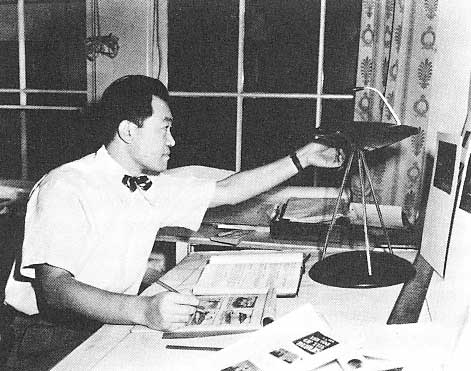

Al Nozaki, a Japanese‑American, made hundreds of sketches to storyboard the script. Shot-by-shot. Hired by Paramount in 1934 to work on Cecil B. DeMille's The Crusades, apprentice draftsman Nozaki spent a year in an internment camp in California before he was released to spend World War II working as an industrial designer in Chicago. Hans Drieir, head of Paramount's art department, rehired him in 1945.

According to George Pal, Lyndon's first script retained the Martian war machines tripod legs. But Pal soon realized that they "just didn't look right." And, for a low‑budget production, the tripods would have cost too much to construct and operate realistically. That's when the idea of basing the machines on a manta ray resting on three beams of pulsating electronic energy occurred to Nozaki,

Nozaki put his design for the machines on paper and had the prop man build a small design model fifteen inches across. Three forty‑two inch models were molded in clay and refined down to Nozaki's specifications. Copper was formed over a wooden armature for the operating models, and each had various mechanisms, lights, and gears to operate the cobra head inside. They were destroyed after the filming.

Art director Al Nozaki with an early model of the Martian machines.

Nozaki is drawing continuity sketches for the production.

The Martian machines were scaled, one‑inch to one‑foot, making an equivalent life size of 42 feet wide and 22 feet high. Each machine had a rotating cobra neck which emitted the heat ray and wing‑tip skeleton rays, but only one machine had the TV scanner probe, and only the main machine could lower its neck as it does when it cinders Pastor Collins. Instead of using three tripod legs that were described in the original novel, three force beams were used to support each machine. When the very first ship appears at dawn, a few shots of the blinking ray-legs can be seen.

The machines were individually attached to fifteen hair‑fine wires connected to a control trolley on an overhead track. Some of the wires carried electricity to operate the interior mechanisms, while others bore the machines' weight.

The triple‑lensed scanner used for close‑ups was made of thick plastic with hexagonal holes cut in it. Behind this, special effects chief Gordon Jennings placed rotating light shutters which gave off an eerie flickering effect.

For the scene in which the machines rise from the gully and are fired upon by the troops, over two, hundred individual explosive charges were placed on piano wires, buried in the ground, or thrown onto the miniature sets by the effects crew. Three lucite domes, the Martians' protective blisters, were filmed against the miniature set while the explosions were triggered. The saucer models, which would have been destroyed by the explosions, were matted in later.

Following Nozaki's design, Gordon Jennings and his special effects crew constructed the machines to project a million volts of static electricity down three wires attached to the floor of the set. A high‑velocity blower was used from behind to force sparks down the electrical "legs." Pal finally decided that the effect, while spectacular, was just too dangerous. It could easily have electrocuted a crew member or set the stage on fire.

The machines' heat rays, which emerged from the cobra head, were burning welding wire. As the wire melted, a blowtorch set up behind blew the wire out, and the result was superimposed over the neck of the machines.

The disintegration of Colonel Heffner by one of the skeleton rays took 144 individual mattes to reduce him to nothingness. In the same sequence a soldier is struck by a heat ray and staggers about the command bunker in flames. The stuntman was "Mushy" Callahan. As actor Les Tremayne (General Mann) recalled, Callahan was wrapped in a blanket to extinguish the flames, but the blanket actually funneled the fire up around his face, and he was badly burned before Tremayne and others rushed in to put out the fire.

A Martian machine blasts a water tower with its heat ray in Los Angeles.

The heat ray was burning welding wire superimposed over the cobra head.

For the destruction of the Los Angeles City Hall, powder man Walter Hoffman placed explosive charges inside the eight‑foot‑tall miniature, and its explosive destruction was filmed by high‑speed cameras.

The unearthly sounds of the Martian machines were produced by amplifying the sounds from three electric guitars played backward. The Martian's scream when Forrester strikes it with the pipe was produced by scraping dry ice across a microphone and mixing it with a woman's scream played backward.

The Martian itself had to be convincing, but there was very little money for anything too elaborate. After Nozaki had come up with a design, he gave it to actor and makeup man Charles Gemora. From paper-mache latex rubber, rubber tubing, and lobster‑red paint over a wooden frame, Gemora fashioned the Martian. With himself inside, Gemora could make the three fingers of the Martian's hand move. With pulsating veins and operational gills in its front, the Martian was weirdly alien‑looking. Unable to walk when inside his Martian construct, Gemora was pulled about the set on a dolly which he knelt on. Extremely fragile, the Martian lasted through its few scenes before falling apart.

Pal hoped initially to film the final third of War in 3-D. When the Earthmen put on their protective goggles, prior to the dropping of the atomic bomb, Pal wanted the audience to put on their 3-D glasses. But Paramount, not incorrectly, believed 3-D was nothing more than a passing fad and vetoed the idea. Perhaps if War and other films that would have benefited from the addition of 3‑D had used the discarded process, audiences would not have thought it such a gimmick.

Low‑budget or not, War of the Worlds still cost nearly $2,600,000 to produce, and approximately $1,300,000 was spent on the special effects. Gordon Jennings, who died shortly after the film's release in 1953, received an Academy Award posthumously for his work on War.

War contained the most extensive and spectacular special effects of any science fiction film since Things to Come in 1936, and shared the decade's honors with Forbidden Planet and This Island Earth.

War places special significance on the number three (perhaps coincidentally), as 2001 would fifteen years later. The meteors fall in groups of three, there are three Pacific Tech scientists in the vicinity, three deputized townspeople stand guard over the meteor, the Martian machines move in groups of three, the Martians have three eyes and three "fingers," and Forrester visits three churches before finding Sylvia in the third.

Pal and Haskin decided early on to have the Martians always in the east and moving toward Los Angeles in the west (screen right to screen left). Little remarked upon, this composition theory gives War an almost subliminal emphasis.

One of the film's first shots, in Linda Rosa, shows the meteor fireball falling from upper screen right diagonally across the screen to lower screen left, exactly bisecting the steeple of a church and providing a subtle clue to the source of the Martians' eventual destruction. A man is shown on a ladder, ready change a movie theater's marquee (the film is Cecil B. DeMille's Paramount production, Samson and Delilah the story of a man with a weakness that destroys him, but not before he destroys his surroundings, as do the Martians.

General Mann, after the failure of the A‑bomb, turns and faces left for a moment, a posture of defeat, then turns back to the right, toward the invaders, and vows to "fight them every inch of the way."

The occurrence of things in threes and the right-to-left emphasis gives War a subconscious correctness and sense of unstoppable advance that helps one become caught up in its relentless pace.

Apart from its superior special effects and manipulative use of screen composition, War is not a very complex film. Byron Haskin's direction, it can be argued, was shaped by Al Nozaki's hundreds of storyboard sketches. But, within the confines of following so detailed a visual blueprint, Haskin's direction is solid and clean. He keeps the action moving at a brisk pace, never allowing it to falter,

The earliest sound pictures, called, appropriately enough, "talkies," lost the art of movement. Tied down to inefficient microphones and huge, soundproofed cameras (see Singin'in the Rain for a comedic look at this problem), the early talkies set back the art of making movies for years until improvements in technology gave back to films their lost freedom.

Under Haskin's sure hand, War moved. His greatest weakness, if the blame can be placed on him, is his direction of the actors. When asked about his two leads, Haskin said, perhaps unfairly, that Ann Robinson was a nice girl and very willing, but not much of an actress. As for Gene Barry, Haskin said, "Jesus, he was terrible! He has since developed into quite an actor, but at that time he couldn't get out of his own way!"

Though Haskin is perhaps too harsh in his judgments about his two leads, he did get excellent performances from Les Tremayne as General Mann and Lewis Martin as Pastor Collins. And, as the three deputized townspeople who become the Martians' first victims, Bill Phipps, Jack Krushchen, and Paul Birch handled their roles nicely.

Gene Barry, born Eugene Klass in 1921, was put under contract by Paramount in 1952 after a successful series of roles on Broadway. War, which was to be his first film, actually became his third, since its late start of shooting allowed Barry to appear in The Atomic City and Those Redheads from Seattle (1952).

War was his only science fiction film until he appeared in John Mantley's thoughtful The 27tb Day in 1957. Always a reliable and steady-working actor,. Barry is best known for three television series: Bat Masterson (1959‑61), Burke's Law (1963‑65), and The Name of the Game (1968‑70).

Ann Robinson, who played Sylvia Van Buren, was born in 1928. Although she'd had small parts in several films prior to War, she had to go through the ordeal of auditioning in Paramount's infamous "fishbowl‑a glass‑encased stage which prevented the actors and actresses from seeing or hearing those scrutinizing them.

Robinson married Mexican matador Jaime Bravo in 1957, but got a divorce in 1967 and never tried acting again. She was a guest at the twenty‑fifth anniversary celebration for War at Hollywood's Holly Cinema in 1977.

Les Tremayne, who played General Mann, was a star of radio drama in the 1940s. Pal chose Tremayne for his authoritative presence and impressive "radio voice." Tremayne has appeared in many films and spoke the narration at the beginning of Forbidden Planet.

Sir Cedric Hardwicke, who spoke the narration, was suggested by Cecil B. DeMille when Pal asked DeMille if he would narrate. Pal later observed that it was unintentionally appropriate that an Englishman narrated a picture based on a book written by H. G. Wells. (For more on the cast, see the Appendix.)

George Pal died of a heart attack at his Beverly Hills home on May 2, 1980. He was seventy‑two. At the time he died, he was working on another film, Voyage of the Berg. He won eight Oscars for his films and was considered a genius in special effects.

Pal will perhaps be remembered more for other films, such as Destination Moon, The Time Machine, and Tom thumb But The War of the Worlds inspired many young filmmakers and made possible many of the special-effects‑laden films being produced today. Dismissed by many as "lightweight," both War and George Pal will continue to grow in stature as long as the wonder of special effects continues to hold audiences spellbound in darkness.

Although produced at a time of hysteria over Communism and the fear of invasion from the skies (see the chapters on Day and The Thing), War has more to do with the genius of H. G. Wells and George Pal than either of those Cold War influences. Its technicolor and effects remain stunning and its low‑budget inventiveness is a tribute to the men who made it. This is one War no one wants to forget.

THE END

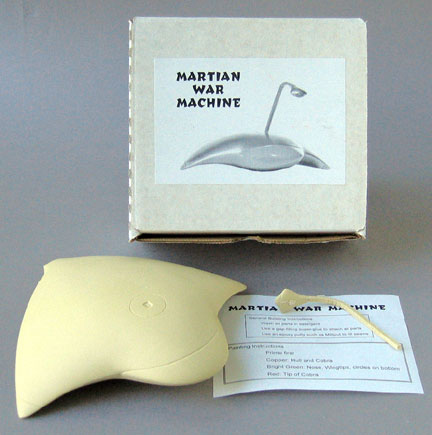

![]()

This model, made by Skyhook Models, is solid plastic and requires relatively little work to finish. There are only two pieces. Instructions are minimal.

![]()

This model was made by Science Fiction Modelmaking Associates. It has been partly assembled and the original parts were made from vacuum-formed pieces. The upper and lower halves of the body came separate and were glued together and the inside is hollow.

![]()

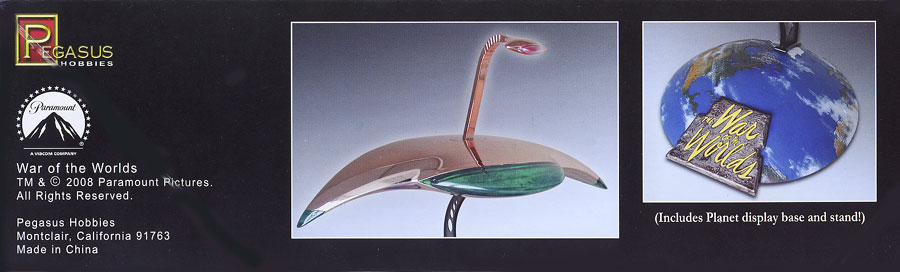

Pegasus Hobbies War Machines

This was the best of all the war machine kits to put together. The plastic parts fit perfectly and needed no reworking. The only item is painting. Gold spray paint is needed to finish the body. The best color recommended by a friend is from Ace hardware and is a metallic gold #17001. I sprayed on a couple of coats sparinglyto avoid runs. The green areas come as transparent green and need no attention. The base that comes with it can also be painted. I could not resist buying three of them because they always worked in groups of threes.

What if the Martians invaded the earth at the wrong time?

![]()

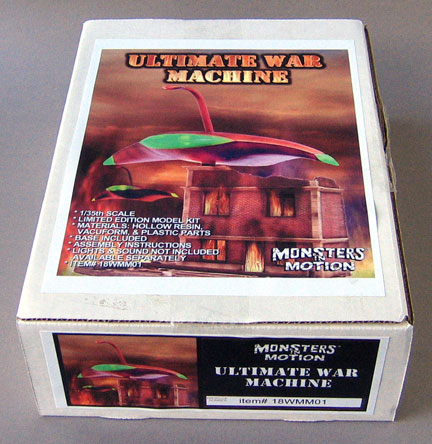

War Machine from Monsters in Motion

|

|

|

This is the most detailed and expensive version of the War Machine that I have seen. It includes not only the machine but also the destroyed buildings and street. Like all other kits, it requires a lot of work, skill and experience to assemble so that it looks reasonably convincing. It requires several special paints, adhesives and an airbrush to do a good job.

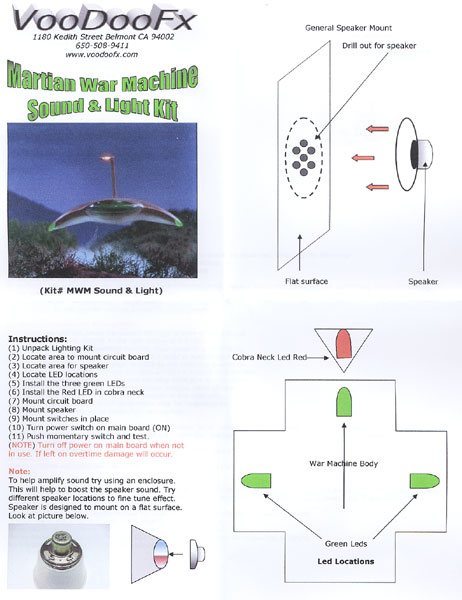

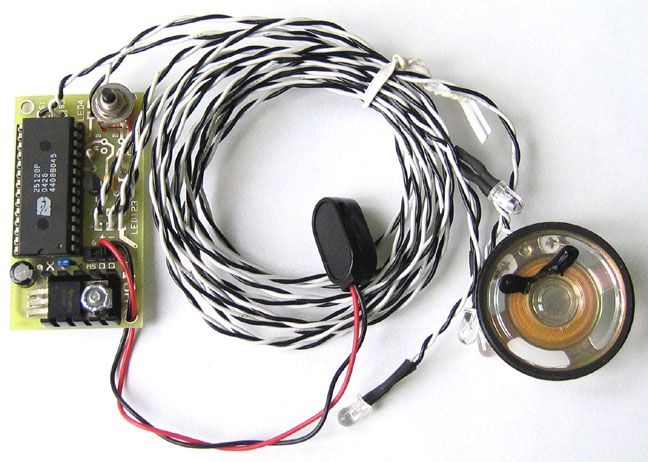

Optional Sound and Light Kit

Most intriguing is the accessory light and sound kit. Three green LEDs are used in the main body and a red LED is used for the cobra heat ray. They flash appropriately. Better yet is the dedicated sound integrated circuit that provides authentic sound from the movie. Instructions are shown above and parts are shown below.

It is powered by a 9-volt battery and includes a speaker. The speaker, battery and circuit board are located in the destroyed buildings. A remote on-off switch can be used as well as the circuit board switch.

![]()

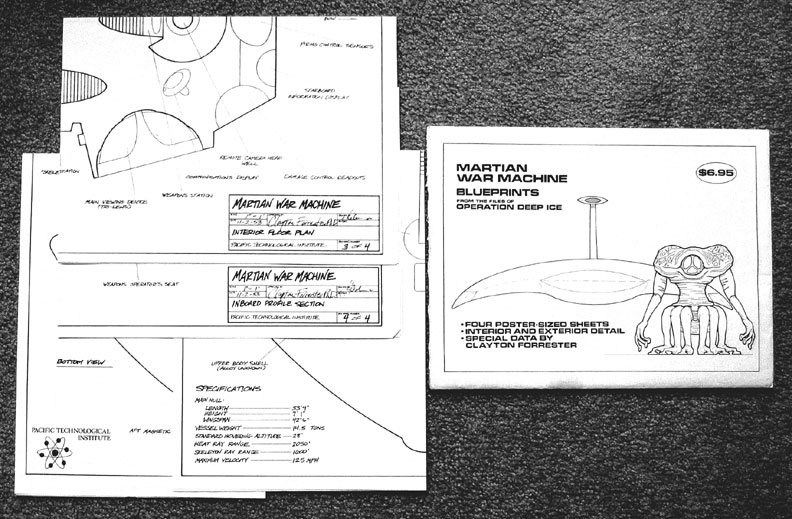

Blueprints were also available including four sheets showing detail and special data by Clayton Forrester.

![]()

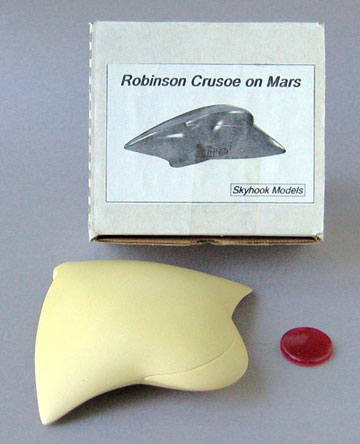

Although the final images of the ships are not shown in the poster, the same manta ray design was used in the movie Robinson Crusoe on Mars but the cobra neck was eliminated and a large red disc was added to the bottom of the alien ship. The tripod circles on the underside were also eliminated. The colors were light pink and light blue instead of a copper body and green wing tips and nose. In addition, some of the same sound effects were used from War of the Worlds.

This model was also made by Skyhook Models and is solid plastic. It requires relatively little work to finish. There are only two pieces. Instructions are minimal.

|

About This Site |

||

|

|

More text and pictures will be added as my research continues. Any contributions, comments, corrections, or additions are welcome. |

|

|

|

|

|