Things to Come

by Roger Russell

This

page is copyrighted

No portion of this site may be reproduced in whole or in part

without written permission of the author.

The first science fiction movie I ever saw was Things to Come based a story by H. G. Wells and starred Raymond Massey as John Cabal, with Edward Chapman as Raymond Passworthy. The film was made in 1936 and the sets were incredibly well made. I was only eight years old in 1943. My mother and I were walking past the RKO Theater in White Plains and I spotted the poster and a few photos from scenes in the movie. I asked my mother if we could see it and we did. I have never forgotten this first experience with a science fiction movie.

Herbert George Wells (1866-1946)

Over the years, I had read several of his stories in a large hard cover book that I got as a present. Later, I saw several other movies made from his stories such as The Invisible Man (1933), The Man Who Could Work Miracles (1936), War of the Worlds (1953) and The Time Machine (1960). Although some of these movies did not follow his original story exactly, they were still some of my favorites and were well done considering the technology of the time. Although there were later remakes of a few of these movies, they departed even more including an overindulgence of special effects.

Things to Come was an excellent combination of

Alexander Korda as the producer, Sir Arthur Bliss for the music and H. G. Wells

for the story. Wells, who was then 68, was determined to make a film of one of

his books. Through his secretary, Russian refugee, Moura Budberg, he met

Alexander Korda. Korda (left) was fascinated by Wells (right) and resolved to

make a film with him. Surprisingly, their first choice was The Shape of

Things to Come. Wells was able to choose Sir Arthur Bliss to write the

musical score. Korda wanted to add the music after the film was shot and

edited. However, much of the finished score was recorded before the scenes were

shot. Consequently, the rebuilding of Everytown by the giant machines was shot

and edited to correspond to the music.

Things to Come was an excellent combination of

Alexander Korda as the producer, Sir Arthur Bliss for the music and H. G. Wells

for the story. Wells, who was then 68, was determined to make a film of one of

his books. Through his secretary, Russian refugee, Moura Budberg, he met

Alexander Korda. Korda (left) was fascinated by Wells (right) and resolved to

make a film with him. Surprisingly, their first choice was The Shape of

Things to Come. Wells was able to choose Sir Arthur Bliss to write the

musical score. Korda wanted to add the music after the film was shot and

edited. However, much of the finished score was recorded before the scenes were

shot. Consequently, the rebuilding of Everytown by the giant machines was shot

and edited to correspond to the music.

Wells knew that the future he predicted in the movie was not a real projection of events the way things would really be. But he was concerned with getting people at least to think about the future and to see that it is a direct result of the decisions we make today. The film opened on February 21, 1936 in London, had excellent reviews, but never earned back the cost of $1,4000,000 to make it. Unfortunately, the film was cut from 130 minutes for the British version to 100 minutes for the US release. It opened at the Rivoli Theater in New York City on April 17, 1936. Things to Come was the most ambitious and expensive SF film ever undertaken until Kubrick’s 2001: A space odyssey, released in 1968.

Although the first part of the movie was nothing but more war, it became most interesting to me when the futuristic scenes appeared. After all, in 1943 we were right in the middle of a real war in Europe and Japan.

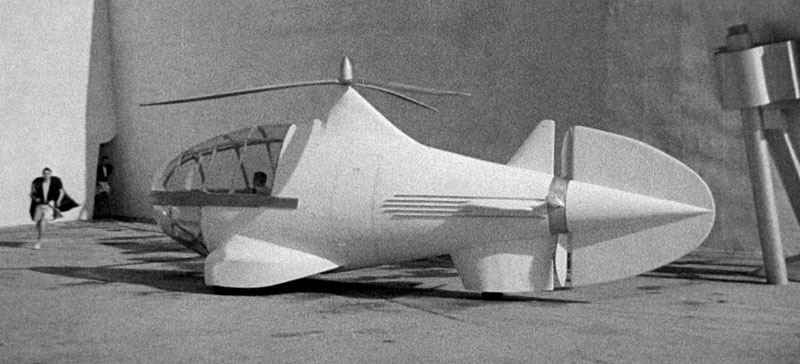

A taste of Things to Come was when Cabal (Raymond Massey) flies into a war-torn town in a small, strange modern-looking plane.

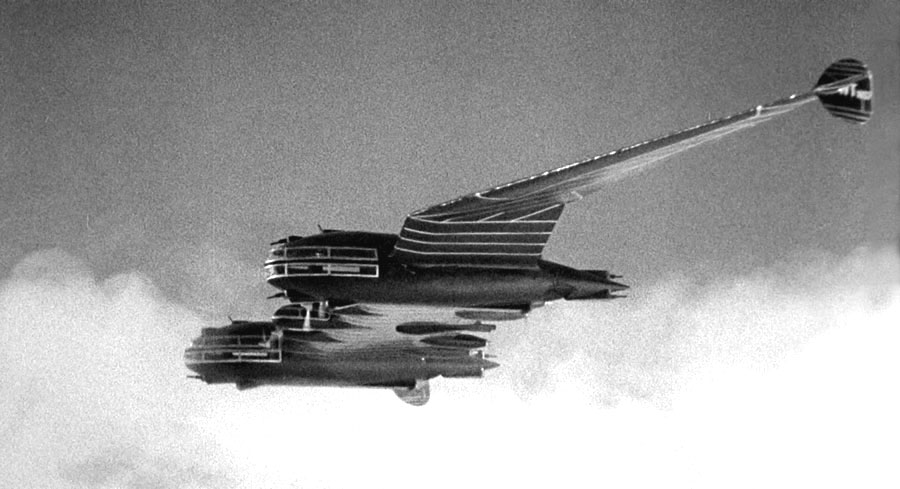

Not long after, out of the distant clouds appears this mind-blowing flying machine.

A whole fleet of Wings Over the World bombers appear in the sky carrying the Gas of Peace.

I remember the sound that accompanied the bombers. It was the low pitched sound made by engines used in zeppelins of that time. The propeller rpm seemed slow compared to large modern propeller planes. At age 8, I was familiar with the normal appearance of bombers and single-engine fighter planes but the appearance of these planes was mind boggling. Like the modern design of futuristic tanks earlier in the movie, I had never seen anything like them before. The scenes came and went so fast I never really had a chance to study all of the workmanship that went into making these models. Of course, there were no computers to generate scenes like this back then. In an earlier scene when the bomber was on the ground being loaded, I could see the planes were really gigantic.

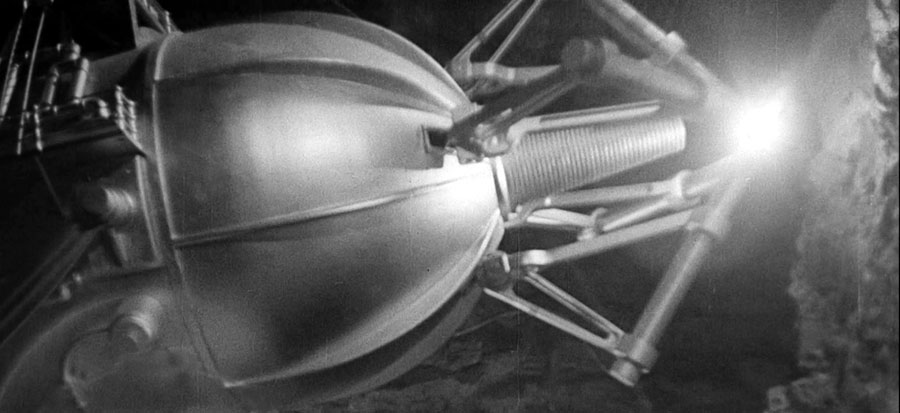

These earth machines look like they focused some sort of plasma into the rock and then the arms spring back tearing out large quantities of rock.

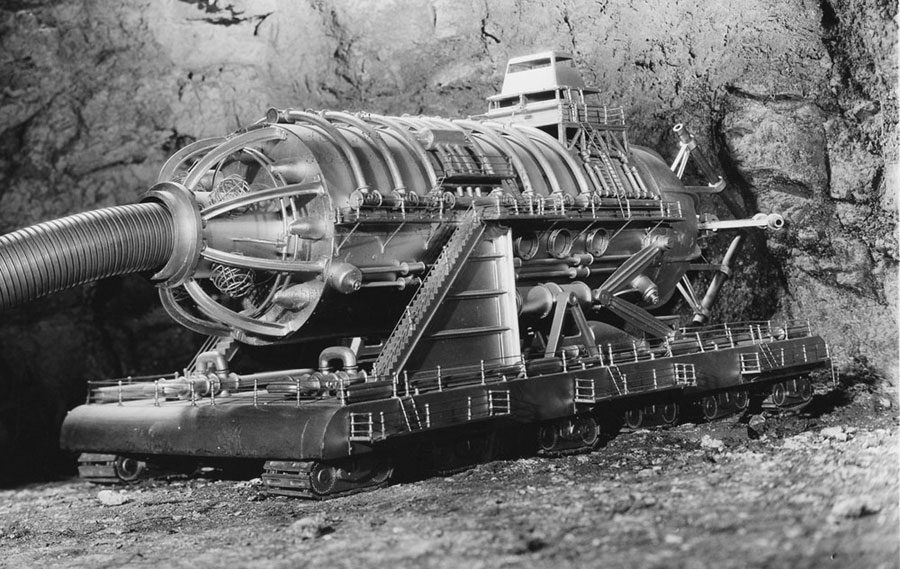

Again, the scenes shifted so fast that I missed the fine detail of this model. It looks like four men at the front railing watching the action.

The whole machine was mounted on multiple treads and actually moved. The large tube at the rear may have been for rock and dust removal. I didn’t remember this from the movie. The top portion of the machine could also be tilted upwards.

After being removed from a giant wall molding machine, another machine lifts the wall to be placed on one of the city apartments. The size is emphasized by the small figures on the several floors.

Futuristic living is in one of the apartments. This may have been a future television like an LCD set or a printed wall decoration. The clear plastic furnishings were also fascinating for me. In the 1930s clear acrylic plastic was invented and known at that time as Plexiglas. It could be shaped into any desirable form and was used in many airplanes.

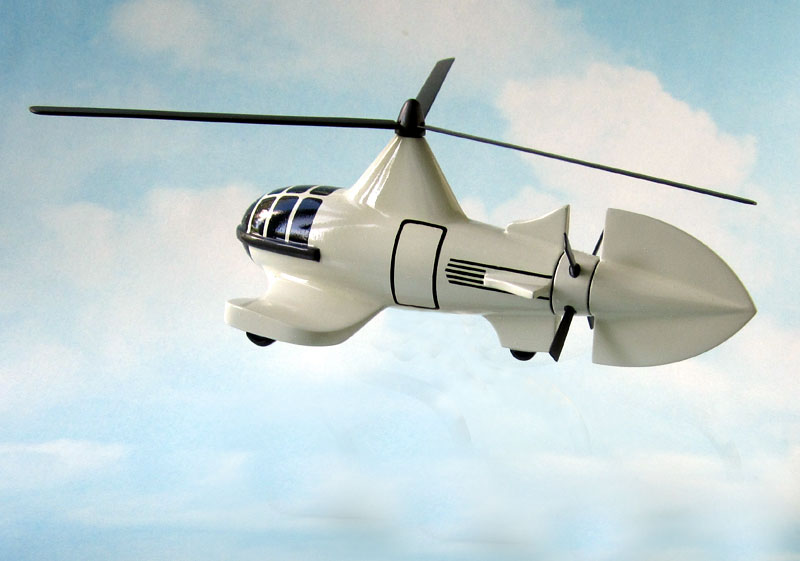

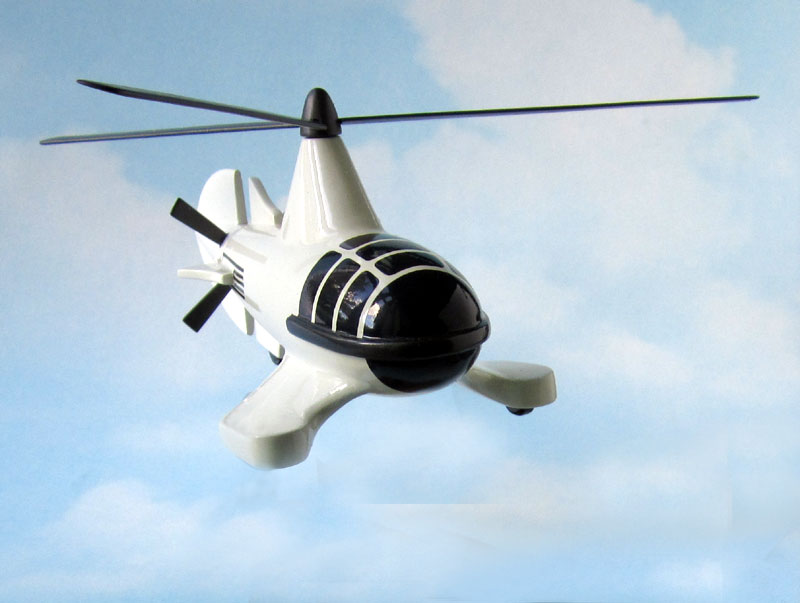

When I first saw the movie in the 1940s, I was very impressed with the Autogyro, also known as a Gyrocopter. Many years later, when viewing the film, I thought it was an impractical movie version of a futuristic helicopter. It was not until I recently researched the term that I found it actually works and the concept is still used today. The main rotor is not powered at all. The propeller at the rear provides air flow to turn the rotor and provide lift. Even if the propeller fails, the descent of the Autogyro will provide sufficient air flow to turn the rotor and enable a safe landing. I would love to have had a model of it to play with back then but it was not until 70 years later that I found a model of it.

“All the universe or nothing—which shall it be?”

Raymond Massey holds the three sections of the film

together, his lean face and frame embodying the will and determination of a man

who has seen too much war and wants to put an end to it forever. His final

speech, to Passworthy, is flawlessly delivered and one of the great moments in

science fiction film. I remembered this long afterwards.

Raymond Massey holds the three sections of the film

together, his lean face and frame embodying the will and determination of a man

who has seen too much war and wants to put an end to it forever. His final

speech, to Passworthy, is flawlessly delivered and one of the great moments in

science fiction film. I remembered this long afterwards.

Passworthy: “I feel what we’ve done is

monstrous!”

Cabal: “What we’ve done is magnificent.”

Passworthy: “If they don’t come back—my son and your daughter—what of that,

Cabal?”

Cabal: “Then, presently, others will go.”

Passworthy: “Oh, god, is there ever to be any age of happiness? Is there never

to be any rest?”

Cabal: “Rest enough for the individual man—too much, and too soon—and we call

it death. But for Man, no rest and no ending. He must go on, conquest beyond

conquest. First this little planet with its winds and ways, and then all the

laws of mind and matter that restrain him. Then the planets about him and at

last out across immensity to the stars. And when he has conquered all the deeps

of space and all the mysteries of time, still he will be beginning.”

Passworthy: “But...we’re such little creatures. Poor humanity’s so fragile, so

weak. Little...little animals.”

Cabal: “Little animals. If we’re no more than animals, we must snatch each

little scrap of happiness and live and suffer and pass, mattering no more than

all the other animals do or have done. Is it this—or that: all the universe or

nothing? Which shall it be, Passworthy? Which shall it be?”

Impressive words and well spoken, but Aristotelian in nature. I shared the enthusiasm and motivation to go beyond nothingness as the alternate, but it offers only two choices and no degrees in between.

Memorabilia

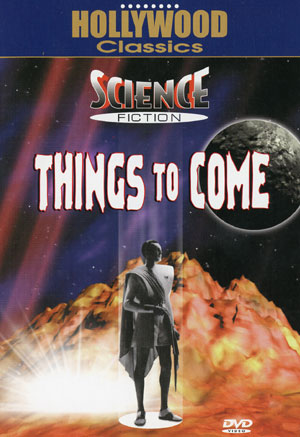

One of

the first DVDs to be released is the Hollywood Classics version in 1999.

It was B&W and 92 minutes long.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Several

other DVDs were released sometimes as a double feature.

The last one, The Shape of Things to Come, is a story loosely based on the HG

Wells story starring Jack Palance.

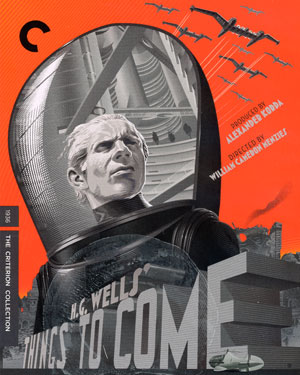

Then

there is the Criterion DVD Blu-Ray release in 2014. It has been reported to be

the best print so far.

This one is also B&W but is 97 minutes long. It includes many extras.

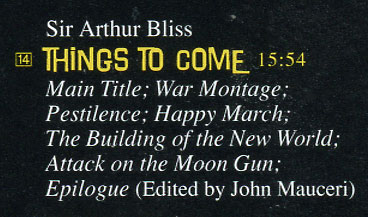

I also found an excellent stereo CD of what appears to be the entire music sound track.

It contains

almost 16 minutes of great sound, far better than the original mono sound

track.

Philips 446 403-2 from 1995

Model of the plane flown by Corbal (Raymond Massey).

This

hard-cover copy was published by Dover Publications, Inc. New York in 1950.

Copyrights listed are: 1895, 1896, 1898, 1901, 1904,1906

1923, 1925, 1928, 1932, 1933, 1934

This paperback copy of 16 short stories was published by Ballantine Books, New York.

Email to

rogerr4@earthlink.net